And Then There Were Only Two

text © Boštjan Videmšek, Maja Prijatelj Videmšek

photos © Matjaž Krivic

Future in the freezer!! How a species of rhinos can be saved in a test tube.

The northern white rhino is all but extinct. The two last males died several years ago. Two females are still with us, but too feeble to bear babies. In an Italian laboratory, their eggs are now artificially fertilised by sperm from the three late males, and kept at minus 196 celsius, in hope that surrogate rhinos from another subspecies can carry the northern white back from the brink.

click to view the complete set of images in the archive

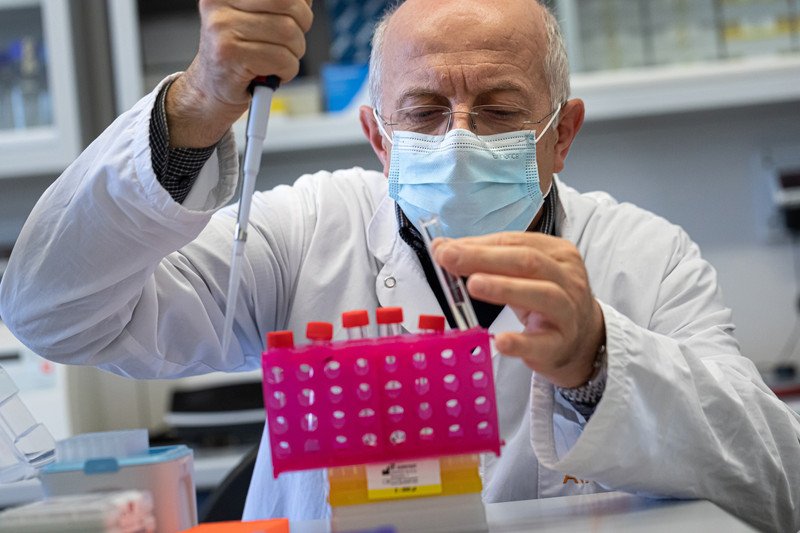

Cesare Galli screwed off the lid of a liquid nitrogen canister and pulled out a sample labelled Fatu NWR x Suni NWR, 9. 4. 21. We were afforded a glimpse of an invaluable rarity: a pair of northern white-rhino embryos, created in March and April at the Avantea lab in Cremona.

Thus far, the Italian lab has managed to create fourteen embryos. The scientists allied with the BioRrescue consortium plan to use them to resurrect functionally extinct species. Only two female northern white rhinos are left: Fatu and Najin. They are unable to conceive in a natural manner.

Mr Galli is impatiently awaiting the arrival of the first northern white rhino baby in twenty-two years. »To the people asking when, I reply: 'In five years’ time...' I've been saying that for a couple of years,« explained the founder and manager of the Avantea biotech company specialising in advanced animal-reproduction technologies and research.

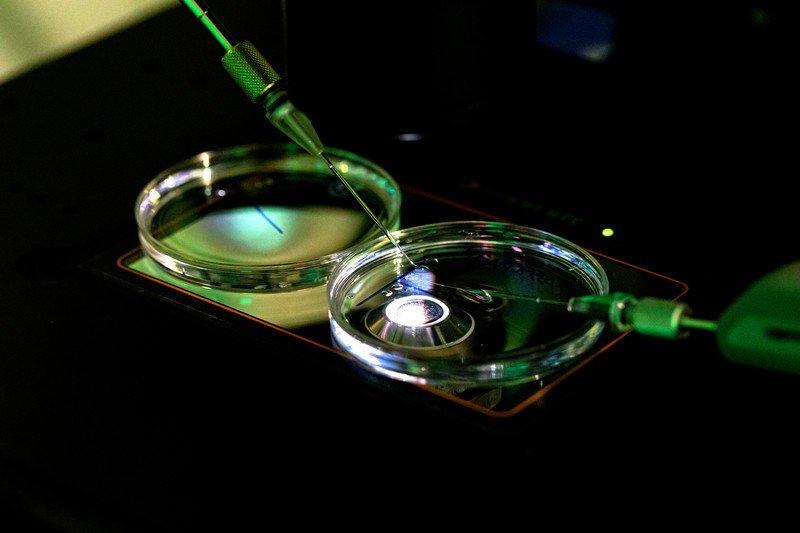

His company was invited to participate in the northern white rhino project on the strength of its two decades in elite-horse reproduction. In this field, Avantea's expertise is second to none, and horses are biologically the most closely related farm animals to rhinos. The Avantea lab was the first to artificially impregnate a mare, using an embryo created through the direct introduction of a sperm cell into the cytoplasm of an egg cell (ICSI technique). This is also currently the most widely used technique for artificially inseminating human beings.

Avantea's experts wasted no time in tailoring the horse-breeding protocol to the needs of rhino-embryo creation. Prior to that, Galli spent several years perfecting the method with the Sumatran and southern white rhinos, though he ultimately failed to produce an embryo. In 2018, he managed to fashion a hybrid embryo between a northern and southern white rhinoceros.

The fourteen northern white rhino embryos created by Avantea in 2019 are currently stored at minus 196 degrees Celsius. In all cases, the role of Eve was played by 21-year old Fatu, a female residing at the Ol Pejeta Conservancy in Kenya, and the role of Adam by two deceased males Suni and Angalifu. The egg cells of Fatu's mother, 32-year-old Najin (also located at Ol Pejeta), proved uncooperative with Avantea's embryo-creation procedures. Due to Najin's age, medical condition and welfare BioRescue team have recently decided to cease harvesting her unfertilised eggs (oocytes) following an ethical risk assessment in 2021.

Since neither Najin nor Fatu can bring them to fruition, the plan is to insert the embryos into southern white rhino surrogate mothers. And this could as much as Thomas Hildebrandt who heads the department of Reproduction Management at Leibniz-IZW institute is concerned, happen soon. “Hopefully, we could do the first embryo transfer in the coming months. All the involved parties have to agree on that, but I think that we have to use the momentum and proceed as soon as possible,” we were told by the German scientist, who has developed the embryo transfer technology and is a driving force of the whole project.

»One female and two males are not enough to foster a self-sustaining population,« Cesare Galli conceded. »But if we create four embryos per year, that makes sixteen in just four years. If we reach a 50-per cent success rate, as we already have with horses, we would have eight new animals. This won't be enough to repopulate the whole of Kenya, but it would be a good start.« ***» When you eliminate a species from the ecosystem, you risk throwing everything off-balance. Rhinos are maintaining the balance. They are also iconic species. And the danger to their survival comes exclusively from us. It is our duty to make amends. The southern white rhinos, for example, we're facing a similar situation. But after South Africa put them under special protection, their number soared to over 20,000. The northern white rhinos had the additional misfortune of all the wars raging in the middle of their natural habitats.« Galli was referring to parts of Uganda, Chad, Sudan, the Central African Republic, and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

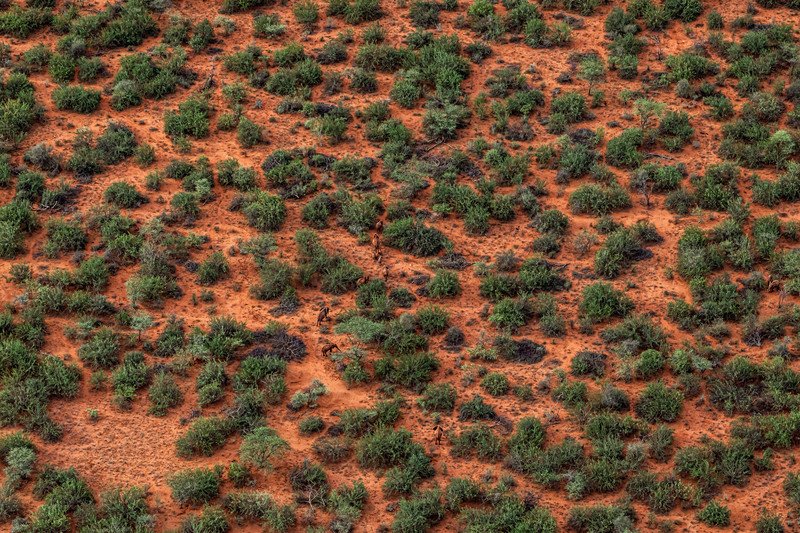

Happy Grazers

The planet's last two remaining northern white rhinos are kept behind three electrical fences and protected by a squad of rangers at the Ol Pejeta Conservancy in central Kenya. Up close, Fatu and Najin seem unperturbed by the wider implications of their species' imminent extinction. Their days follow a simple and uneventful routine. Their nights are spent in their snug straw-covered pens among a host of whistling thorns (Vachellia drepanolobium). From about six to nine, they can be found grazing along with their approximately 2.8-square kilometre enclosure. Once it gets too hot, they fill their bellies with water and lie down to rest, only to resume their grazing when it gets a bit cooler. They adore rain, impromptu mud baths and sharpening their horns on nearby trees.

Zachary Mutai, their head caregiver at the Ol Pejeta Conservancy, described them as 'happy slaves of routine'.Asked about what makes them happy, Zachary reflected for a moment: »Food is very important.« Bales of straw get Najin and Fatu through the dry seasons, while carrots are their equivalent of a quick fix (two kilos a day).It would be impossible not to be impressed by Zachary's commitment to his wards. Najin, the older of the two rhinos, seems to adore him stroking her behind her ears and along her flank. Fatu's moods are harder to predict, so he prefers to keep her at a distance.

While it is true that as the second biggest land mammal, the two girls could snuff him out in a heartbeat, this is far from the sole cause of his humbleness. He keeps cooing to them and never raises his voice. After years of spending more time with them than with his family, he is intimately familiar with their every habit.

While talking to us, the short but immensely spirited caregiver seemed to be drinking in the natural sounds from our surroundings. As a great expert on birds, he never gets bored while Najin and Fatu graze. As we trailed the pair of huge walking lawnmowers occasionally letting out a wet fart, Zachary would often halt, lift a finger, and hold forth on the nature of the bird currently making its presence felt.

There was also the sound of lions roaring in a distant thicket, and some monkeys gibbering not too far off. Zachary directed our gaze to a flock of ostriches practising sprints. He can spot rhinos from more than a kilometre off with his naked eye.

Zachary had always wanted to become a conservationist. »I grew up north of the Masai Mara national reserve, where we had plenty of wild animals. Ol Pejeta was previously a cattle ranch, where my father used to work. When the ranch started expanding into wildlife preservation, I jumped on the opportunity to get a job. At first, I oversaw the electrical-fence maintenance, but I rose to the position of head caregiver to the rhinos. I have been doing this for over ten years.«

Refugees

Najin and Fatu's story was born at the Dvůr Králové Safari park in the Czech Republic, which remains their legal owner. Both are descended from the last northern white rhino male named Sudan. Najin is his daughter, while Fatu is his granddaughter.The two of them, along with a male named Suni, were transferred to Ol Pejeta in 2009, in the hope that returning them to their natural habitat might help them regain their zest for life and reproduction.

Very little went according to plan. The three imported rhinos and Sudan did mate but to no avail. In 2014 Suni passed away of natural causes, aged 34. On March 18, 2018, Sudan, the last northern white standing, collapsed and couldn't get up. The day after, his severe pain forced the Ol Pejeta staff to put him to sleep.

To hear Zachary tell it, it was like their whole world went dark. »All of the caretakers were crying. I was fortunate enough to spend his last moments by his side. He was a friend to so many people here.«

In 2015, Czech vets confirmed Najin and Fatu were no longer able to propagate in the natural fashion. All the years Najin had spent in a cage had weakened her hind legs to the extent she is no longer able to withstand the male's weight. An ultrasound scan detected a large cyst on her left ovary and several small, benign tumours on the cervix and uterus. Fatu was diagnosed with pathological degenerations in her womb.

»Their reproductive capacity is severely diminished,« said Stephen Ngulu, head veterinarian at Ol Pejeta. »But they’re in pretty good health.«

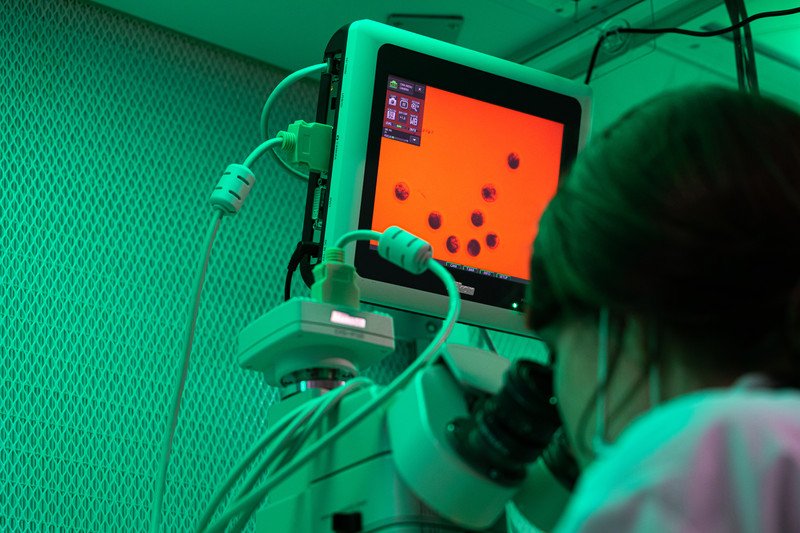

In 2015, a group of 20 scientists hailing from five continents drew up a rescue plan for the northern white rhinos. Only three – Najin, Fatu and Sudan – were alive at the time. The only course open was a combination of complex and expensive stem-cell technologies, which had the additional disadvantage of never having been tested on rhinos. Even securing the oocytes from the two female rhinos was a breathtakingly challenging enterprise, given that rhino ovaries are not much larger than a human fist.

The process is also quite taxing on the two female rhinos; so taxing they have to be heavily sedated. Yet every single part of every procedure has been harmonised with the goals of ethical risk assessment.

Ethical risk assessment

A thorough review determined the process of gathering oocytes has no significant impact on Fatu's wellbeing,« Stephen Ngulu assured us with conviction.Four surrogate southern white rhino mothers, who had already managed to reproduce in the past, are already in residence at Ol Pejeta. Prior to embryo insertion, scientists still must do extensive research into their reproductive cycles.

The idea is to first insert a southern white rhino embryo, and if it takes, its northern white counterpart should follow. The covid pandemic put a temporary stop to the project, but the Ol Pejeta staff are confident the first embryos will be inserted within the current year.

»The assisted-reproduction technology is sure to bring mid-term results – the embryos we created are alive,« Cesare Galli assured us. There is also an alternative: raising reproductive cells from induced pluripotent stem cells, harvested from the preserved tissue of deceased northern white rhinos. Leading the field in the artificial creation of reproductive cells from stem cells is Katsuhiko Hayashi from Kyushu University in Japan. ***» It's an expensive project. Many people are saying it's not worth it, saving a single species while thousands of others are dying out. We disagree,« said Richard Vigne, Ol Pejeta's CEO until recently. According to him, the northern white rhino project has already brought tremendous global attention to animal extinction issues.

»Sudan has been turned into a global icon!« Vigne exclaimed. »This was a huge win for conservationism!« The Ol Pejeta territory used to be a cattle ranch in colonial Kenya. It was separated into several fenced-off plots where the livestock used to graze. All the wildlife straying into the compound got exterminated. Following Kenya's 1977 ban on wildlife hunting, the animals – especially elephants – began returning to the area. With the additional financial strain this put on the ranchers, the decision was taken to start branching out into tourism.

In 1988, the ranch founded the Sweetwaters Game Reserve and started filling it up with critically endangered black rhinos. This move coincided with the Kenya Wildlife Service ruling that all black rhinos should be moved to game reserves. The starting population at Sweetwaters was 20 black rhinos. Today the number stands at 149, and Ol Pejeta is firmly established as the largest black rhino sanctuary in Eastern Africa.

Vigne first took over managing the ranch, and then the entire conservancy. His reign brought about a successful business model, cojoining livestock ranching with conservationism and tourism: »We employ about a thousand people, we pay a lot of taxes, and we're helping to maintain the ecological equilibrium. For our local community, this is a win-win!«

The recent pandemic took a heavy toll on the conservancy's touristic income. »115,000 people came to visit in 2019, while last year we've only seen 30,000,« Vigne shrugged mournfully. »And 56 per cent of those were locals, who spend much less. The projection was that tourism would bring around 12 million dollars last year. But it only brought 1.6 million.«

Kenyan approach to rhino conservation has proved successful. For the past few years, the population has been expanding by five to seven per cent. 2020 marked the first time in two decades when not a single rhino was shot in the country. At Ol Pejeta, this has been the case for three years.

Now, the Conservancy is home to 190 rhinos. »Kenya did a hell of a job with regard to elephant and rhino protection,« Vigne nodded. »This is especially true of the period following 2014. Most of the rhinos here die of natural causes, though you must remember they're only able to live in a protected environment. Poaching is no longer our main concern. That distinction has now gone to lack of space.«

With regard to black rhinos, Ol Pejeta has already surpassed its carrying capacity. Therefore, the management opted to purchase an additional 20,000 acres of land from the local community.

The main reason for the rhinos doing so well in Kenya is the combination of the wildlife-hunting ban in the seventies and the 2013 legislative update sentencing anyone caught with a rhino horn (or an elephant tusk) to life imprisonment or a fine of 20 million Kenyan shillings. There is a lot of political will to preserve the rhinos in the land, and the general public's awareness has seen a rise.

Yet Kenya is really but an islet within an Africa still heavily infested with poaching, most of it directed by Asian organised crime groups. In the wake of the poaching crisis claiming as many as 1324 rhinos' lives in 2015, the number dropped to 435 dead rhinos in 2020. The overwhelming majority (394) was felled in South Africa. The country not only supports the globe's largest rhino population but also condones trophy hunting of rhinos and elephants. Its private reserve parks are used to breed fresh fodder

Of all twenty-two, deceased animals, only two – Sudan and Suni – died of natural causes.

Rhino’s Cemetery'Born May 17, 1996. Died February 22, 2016,' reads the inscription on the tombstone of a female black rhino named Ishirini. 'Probably killed by a poison dart. A security team found her in great pain, with horns already cut off. She was twelve months pregnant.'

Zachary Mutai held up a tenuous fibre he picked off Najin's smaller horn. »They're hunting them for their horns, which are nothing else than keratin our nails and hair are made of!«

The members of the nouveau riche set in China and Vietnam consider the horns as a sort of panacea. And they are not the only ones. In their eyes, rhino horns can do anything from boosting potency and curing cancer to helping one glide through a hangover.

A kilogram of the horn is currently worth 65,000 US dollars on the Asian black market. ***While driving around Ol Pejeta, we spotted the youngest of the southern white rhinos, born this March. The still hornless grey fellow seemed at the height of playfulness. He kept kicking and ramming into his parents, grazing stoically in the dusk. Until the mother finally had enough and pushed him away with her horn, sending the baby flying at least a meter to the side. It was to no avail. After he picked itself up, his evening frolic went on undeterred.