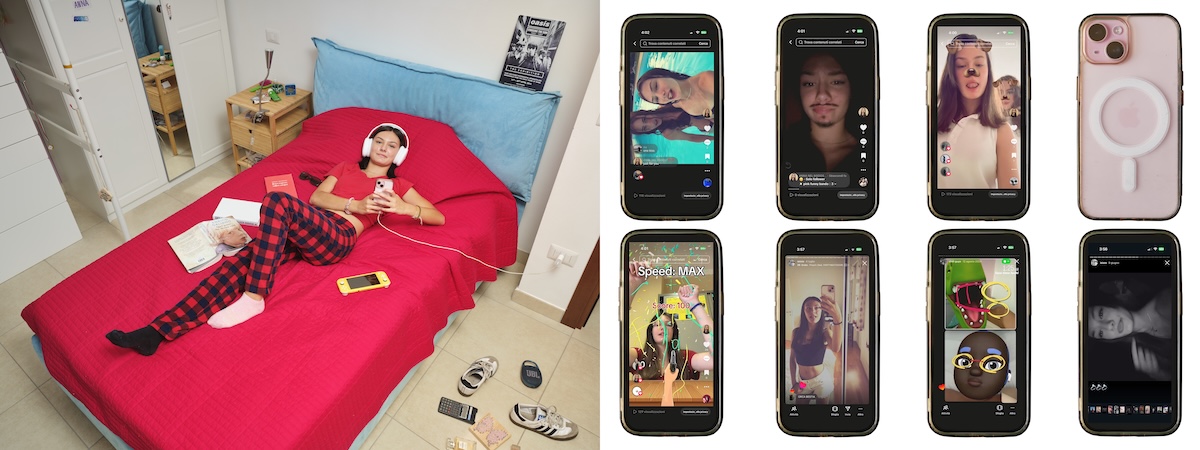

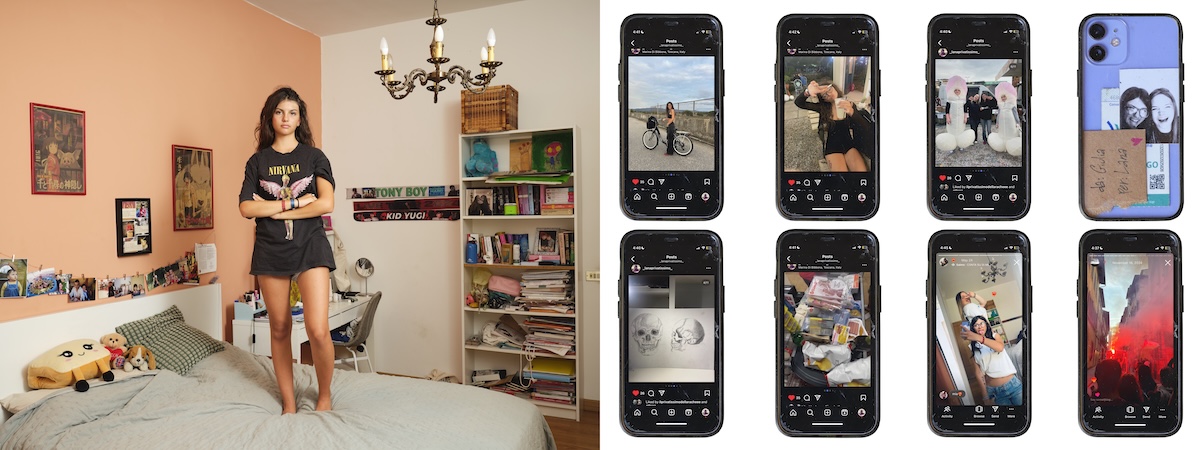

IRL (In Real Life)

© Niccolo’ Rastrelli

IRL (In Real Life) is an ongoing photographic project that explores the identity and representation of Generation Z — the first to grow up in a world where real and digital life merge seamlessly, redefining boundaries, relationships, and forms of personal expression. Through a documentary and intimate approach, the project portrays young people within their most personal spaces — their bedrooms — juxtaposing these portraits with images taken from their smartphones: selfies, stories, posts, and screenshots that shape their online presence. Two visual worlds, one physical and one digital, intersect and overlap to authentically narrate the complexity of contemporary youth.Born between the late 1990s and the early 2010s, this generation uses images as a language — a tool for identity and belonging. IRL observes how, from Milan to Delhi, Nairobi to Buenos Aires, the same digital gestures and symbols have become a global code, while still reflecting different cultures, dreams, and contradictions.

The project’s ambition is to expand across all continents, building a visual archive capable of capturing both the universal and intimate dimensions of a connected generation. In the long term, IRL will evolve into a series of international exhibitions and a book — creating a space for dialogue between young people and adults, cultures and languages, the real and the virtual.

click to view the complete set of images in the archive.

The Art of Hollywood

© Julia Fullerton-Batten

2026

Before green screens.

Before pixels replaced paint.

There was an illusion, made by hand.

At a time when the movie industry is ruled by digital perfection, I turn my camera toward what came before: a Hollywood built on canvas, pigment, and the invisible labour of master painters who created entire worlds behind the actors.

I travelled to Los Angeles to stand before these monumental, long-forgotten backdrops, survivors of another era. Once central to cinematic storytelling, they now linger in silence. By entering these painted spaces, I reanimate them, staging new narratives that resonate with the films we thought we knew, yet remember only in fragments.

The Art of Hollywood is a return to the age of hand-painted film posters, images that promised everything in a single frame: love, danger, glamour, escape. Borrowing their visual language, I construct carefully choreographed scenes in which reality and illusion collapse into a single image.

This work is not a homage.

It is a confrontation.

A dialogue between analogue craftsmanship and contemporary vision.

Between memory and reinvention.

Hollywood, once painted.

Hollywood, remembered.

Hollywood, reimagined.

click to view the complete set of images in the archive

Before green screens.

Before pixels replaced paint.

There was an illusion, made by hand.

At a time when the movie industry is ruled by digital perfection, I turn my camera toward what came before: a Hollywood built on canvas, pigment, and the invisible labour of master painters who created entire worlds behind the actors.

I travelled to Los Angeles to stand before these monumental, long-forgotten backdrops, survivors of another era. Once central to cinematic storytelling, they now linger in silence. By entering these painted spaces, I reanimate them, staging new narratives that resonate with the films we thought we knew, yet remember only in fragments.

The Art of Hollywood is a return to the age of hand-painted film posters, images that promised everything in a single frame: love, danger, glamour, escape. Borrowing their visual language, I construct carefully choreographed scenes in which reality and illusion collapse into a single image.

This work is not a homage.

It is a confrontation.

A dialogue between analogue craftsmanship and contemporary vision.

Between memory and reinvention.

Hollywood, once painted.

Hollywood, remembered.

Hollywood, reimagined.

click to view the complete set of images in the archive

White Water

© Charles XelotThe Arctic Ocean is a territory where man has no place: here, there is no life, only survival. Between October 2021 and May 202,2 I travelled in and around the Russian Arctic Ocean. I boarded four ships, visited five ports and met hundreds of people.

Explorers, artists and poets have fantasised about the Arctic. This immensity, immaculate and deadly, has always attracted adventurous spirits, those who wanted to touch the very edge of the world, test their own limits, and find breathtaking inspiration. Many men and women have given their lives for the thrill of discovery, to be the first to reach these places and make history. Making a new crossing, discovering a new island or simply surviving the winter were feats in themselves.

We now live in an age of exploitation and tourism. Adventure has been tamed, rationalised and organised. Commercial shipping has imposed its economic and safety standards because the industry needs certainty and results to justify its colossal investments. The huge ships that ply the Arctic Ocean carry gas, oil or building materials - all the power of human technology is brought to bear to cross the ice. Nations competed, and the goal was no longer glory and territorial conquest but market share and economic influence. Geography gave Russia an enormous advantage: it had the longest Arctic coastline and the only commercially exploitable sea route.

Thousands of anonymous men sail along the capes named by the explorers of the past. These ice sailors cross space in gigantic steel boats. The men survive protected by the ships' shells, while outside, the omnipresent white and merciless cold stretches to infinity.

The sailors live cut off from the world, moving around without travelling and working non-stop. Monotonous days follow one another, with the same routine, the same colleagues and the same dangers. There area few distractions on board. Only the landscape varies: the ocean comes in thousands of shades, from the darkest grey to the most dazzling white. The sky is full of it, exploring every variation of pastel in endless sunsets.

Through Xelot’s photographs, he wanted to explore this life frozen in white. “I wanted to show the poetry of these sailors sheltered in their ships, living in the great beauty of the Arctic, but also cohabiting with its harshness. There is a paradox between the inhospitable environment and the sometimes boring comfort of heated cabins.”

Despite the geographical isolation of these regions, people are connected, and the world's major events reach them. First, it was the Coronavirus that physically disrupted the work of Arctic sailors. Then, on 24 February 2022, the world changed: the war had begun. On board the ships, sailors of all ages and political persuasions rub shoulders, Ukrainians, Russians and Belarusians. Normally, cohabitation went well, and politics did not affect relations. But after 24 February, tempers flared, and the tension became palpable. Almost all the discussions revolved around the same subject, and the sailors quickly grouped by affinity of thought. Some, whose families were directly affected, sank into silence, while others belched, almost happy to see this war finally begin.

“During the months I spent on board various ships, I met some fascinating men, men of the sea. They shared their daily lives with me, both ordinary and extraordinary. I was able to feel the bite of the cold, eat good meals, burn my eyes on the infinite whiteness and play ping-pong, embrace the icy depths of the Arctic night and feel the relief of a warm bed in the middle of the ocean void.”

“I often think of them, of my friends who stayed on board. I think of our conversations, their hopes, their doubts and the great white we shared.” - Charles Xelot 2026

click to view the complete set of images in the archive

Too Many Man: Women of Grime

© Ellie RamsdenToo Many Man: Women of Grime documents women involved in the UK grime scene, showcasing those behind the mic and behind the scenes, from MCs and DJs to producers and journalists. Since the genre began in the early 2000s, grime has been hugely male-dominated. Like many male-dominated spaces, women have a significant influence on the scene but often aren't given the same platform or recognition as their male counterparts. This project seeks to ask why and gives the women of Grime a platform to share their thoughts and experiences.

The project title is named after the 2009 song ‘Too Many Man’ by Skepta, in which the grime MC expresses his frustration with the “lack of women in clubs”; this is re-conceptualised as a comment on not only the club scene but a wider observation on the genre itself.

First published as a photo-book in 2019, a second edition was released in March 2021 and includes new and updated content. The project comprises portraits, interviews, handwritten lyrics, live music shots, and urban landscapes.

click to view the complete set of images in the archive

Elvies

© Ellie RamsdenEvery year, 40,000 Elvis impersonators and fans descend on a small seaside town in South Wales to celebrate the rock legend’s life and music. Powthcawl, a seemingly unlikely place to host the largest Elvis Presley festival in the world, gives a surreal backdrop to the weekend.

Organiser, Peter Phillips, started the Elvis festival two decades ago to raise money to save the local theatre, the Grand Pavilion. Just 500 people attended the event the first year - now, the whole town is taken over for the weekend. Every pub books Elvis impersonators, and revellers dress up in costumes. There's a Young Elvis competition, and a 'Hound Dog' prize for the best-dressed mutt.

The festival offers a weekend of escapism to our often serious and stressful realities. Become Elvis and let all your worries wash away!

click to view the complete set of images in the archive