Backstage Fashion

© Just LoomisIn 1969, I was twelve years old, watching my mother in the mirror as she tried on a dress in the department store, I. Magnin in San Francisco. I knew how much she loved shopping at the upscale department store. In Reno, where we lived, she could not find her favorite designers: Valentino, Yves Saint Laurent, and Gucci. We came here nearly every weekend so she could shop and my father could sit in the bar across the street at the Saint Francis Hotel. I had to dress in new penny loafers, gray flannel pants, and a blue blazer. After she made her purchases we would walk back through the streets to the Saint Francis with big pink-and-white, I. Magnin shopping bags. My mother would remove her hat and settle in at the bar, choosing a chair where she could watch herself in the mirror. At night, my brother Drew and his wife Suzanne would take me to the Fillmore West in San Francisco to see Janis Joplin or the Jefferson Airplane. As they danced under the blacklight I would wander off and look at the people. I went up to the balcony to the row of overhead projectors throwing the psychedelic colored shapes on the band. There was also a row of film projectors with loops playing the same scene over and over. I remember one of a woman in a room, unbuttoning her blouse, slowly undressing. I looked down at the band and psychedelic light show and saw my brother and Suzanne with all the people dancing in the wild colored clothes. It was an entrancing ritual. I will never forget it.

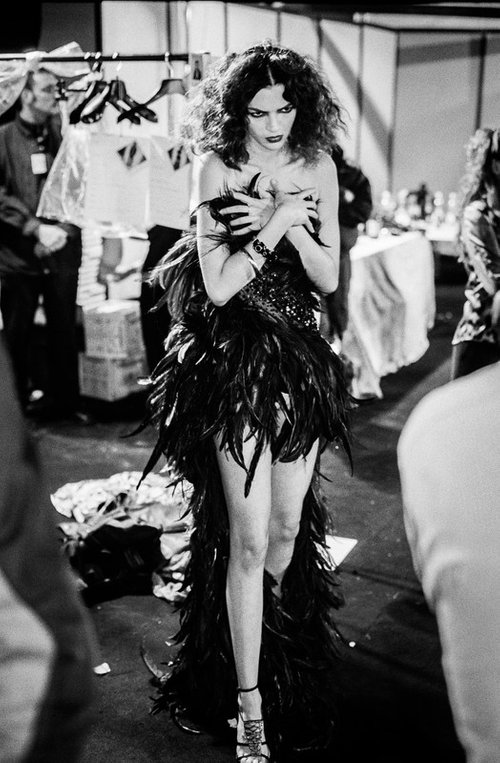

My mother was a local theater actress. She was glamorous and self-obsessed. We subscribed to all the fashion magazines: Vogue, Bazaar, and Mademoiselle. She had a closet full of luxurious designer dresses, hats, handbags, and over two hundred pairs of shoes. As a kid, I passed many hours near her, fascinated by her image in the mirror as she dressed and put on her red lipstick, getting a thrill if she looked my way. She wore her Valentino through the streets and across the floor of the Reno casinos. It was a real scene. My parents often went out to see a floor show. Sammy Davis Jr. or Liberace—always with the Showgirls in their fishnet stockings, makeup, and feather boas. Often, I went along for the dinner show. Our table was very close to the stage and I remember seeing clearly, the perspiration on the Showgirl’s face and the details of her shoes. The Nevada Showgirl was familiar and everywhere: in newspapers, on billboards, and twenty-five feet tall, with arms raised high, rotating over the door of the Primadonna Casino. While at boarding school, I picked up a camera. I escaped my life at school and wandered the roads by myself, taking pictures. I connected to a world of my own through the intimacy of photography. I realized I could live and interpret the world with the language of the camera. I spent countless hours working in the darkroom, developing the beautiful blacks and greys of the silver gelatin print. I went on to learn commercial photography at the Art Center in Los Angeles. I studied the great fashion photographers of the time: Irving Penn, Richard Avedon, Guy Bourdin, and Helmut Newton. I was obsessed with looking at the models and photographs in Vogue.

All I wanted was to be a fashion photographer. I had grown up with it. While at school, I had great luck meeting Helmut Newton. I wrote him a letter saying I’d do anything to be his assistant. I got the job. I was allowed behind the scenes, I entered his world. I worked closely with him as he constructed his elaborate shoots for Vogue, Vanity Fair, and Karl Lagerfeld. I absorbed everything, as he manoeuvred the models and stylists to get what he wanted: the image in his head. I helped him with private sittings: a portrait of Timothy Leary or a rich Hollywood housewife. It was a luxurious world, and I felt very fortunate. Helmut and I became friends. He and his wife June were wonderful; they invited me to parties and let me in. We hung out at the Chateau Marmont in Hollywood and talked about photography. Sometimes he would look at my work and give me advice, “Maybe you should go to Milan. I hear they’re open to giving young photographers a break.”

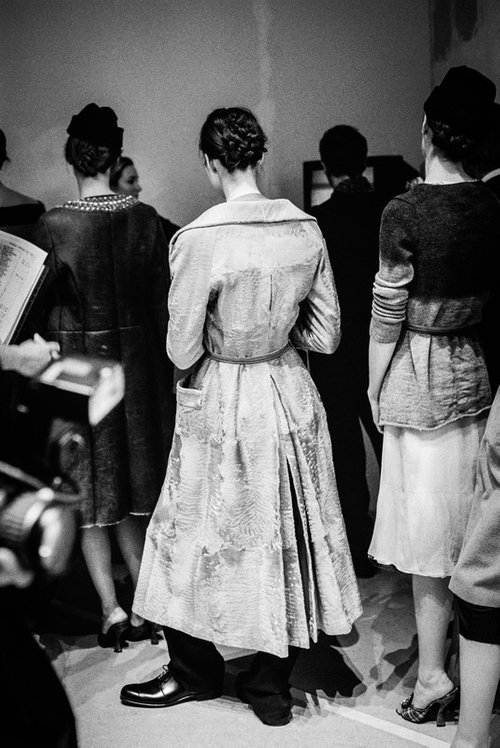

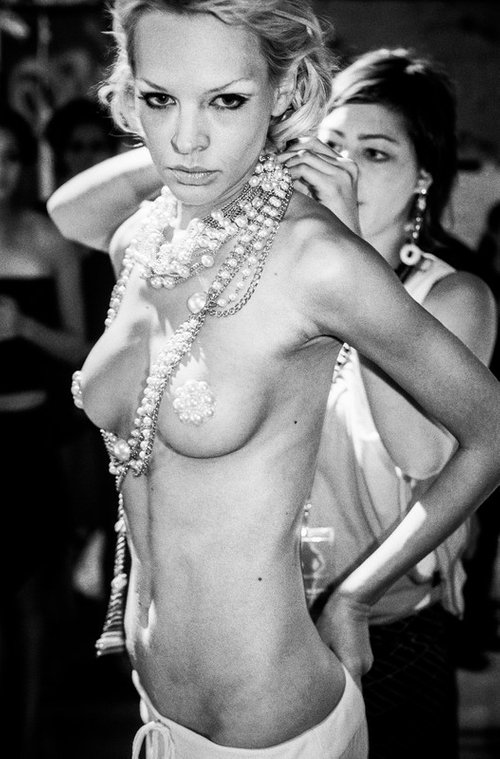

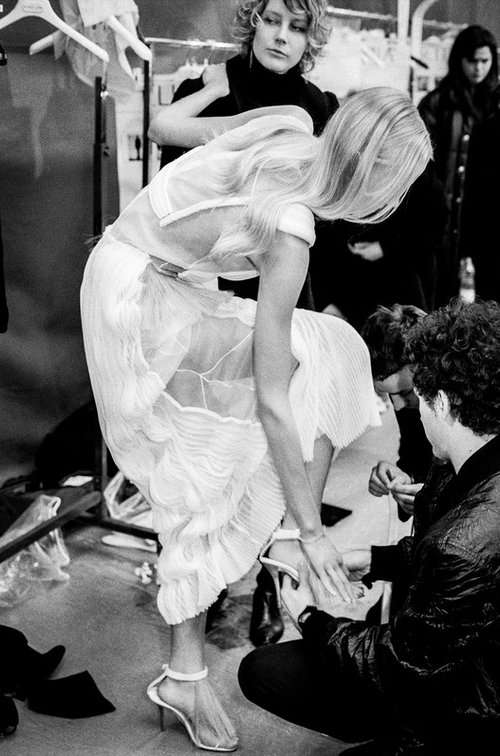

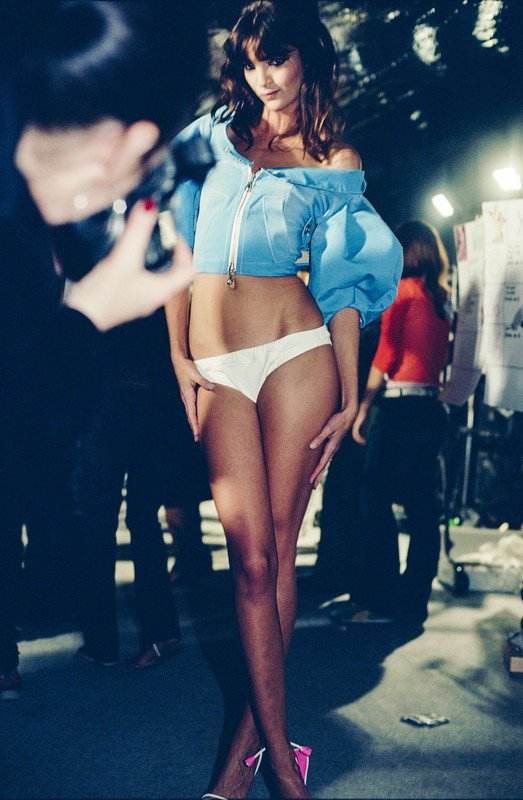

In 1981 I moved to Milan. I was speechless walking across the Piazza del Duomo. I had never seen anything like this in America. I was in a new world and I loved it. I was out of my element and knew I had to start, photographically, from scratch. I went through a long period of introspection and thought about my strong desire for intimacy. I wanted to make what I called a “fashion portrait”: to see not just the model, but the woman. I wanted authenticity and worked for two years on this idea, photographing every model I could find. Milan was full of young fashion hopefuls. I shared an apartment with my photographer friend and slept on a foam pad behind a couch and photographed every day. I was friends with the hairstylists, makeup artists, and models. We lived out of each other’s pockets and helped each other. We worked long hours collaborating on “test shoots.” I made dozens of prints and took hundreds of Polaroids that I showed to Carla Sozzani. She assigned me my first story in Vogue Sposa. Two years later, I arrived at the fashion shows in Milan. The first thing I saw was two famous models drinking cappuccino by themselves at the bar. I went right up and talked to them. I couldn’t believe it. I could never talk to these models. They were always surrounded by the Italian playboys. I learned about these guys when I first arrived in Milan and stayed in the Residence Clotilde, where all the struggling models and photographers lived. The playboys hung out in the lobby and greeted the models as they arrived vulnerable and fresh off the plane. They were relentless in their pursuit of the young girls. Once, I talked to one of their models and three of them bullied me into a corner. Thankfully, there was no sign of them that day at the fashion shows, hanging around, aimless while the models were working. As the models headed off to get dressed I followed. I stayed close, right next to them as we walked through the door by the security guards. When I looked up I was backstage, I stood still, in awe as if in a dream. Beautiful half-dressed women were silhouetted by blue industrial lights, some in long white Gianfranco Ferré gowns, others dancing and drinking champagne. Smoke from the cigarettes lingered in the air like a mysterious veil pulling me in. I immediately felt comfortable. I had seen models like this working with Helmut, but there was also the hand of my mother and the Showgirl, reaching out, pulling back the curtain, leading me on.

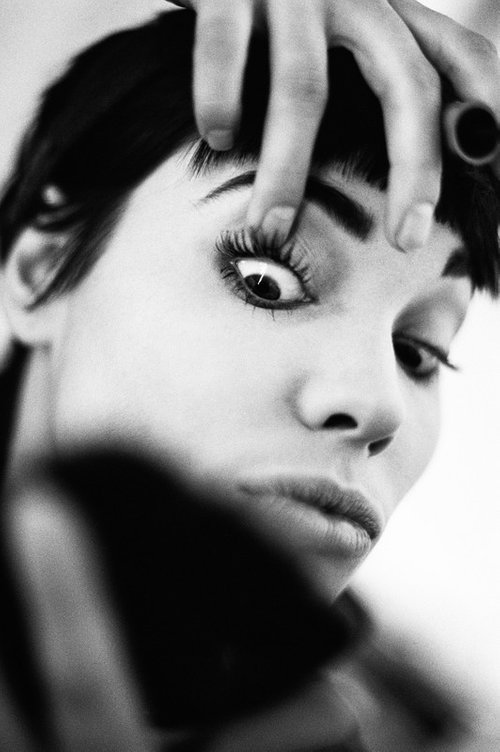

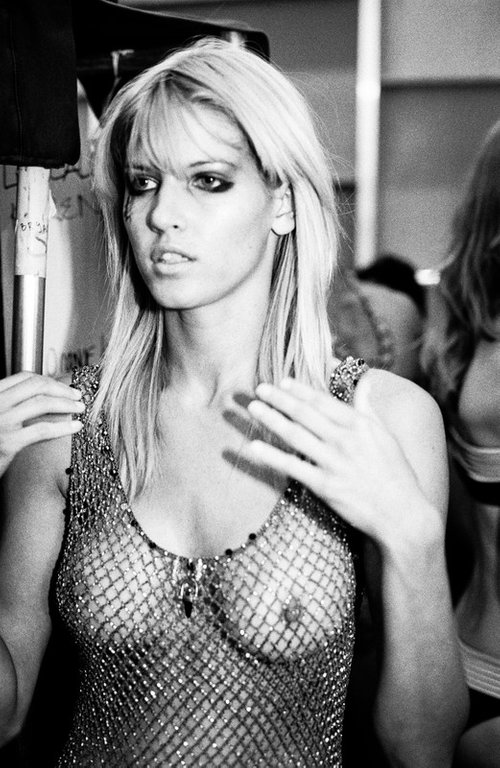

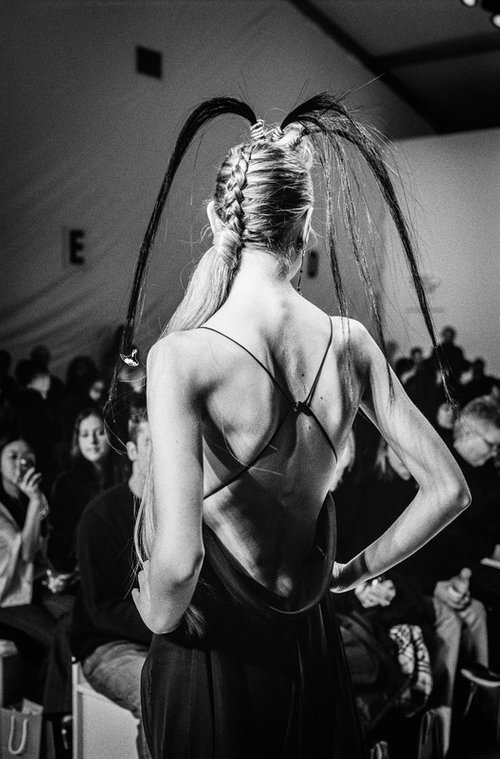

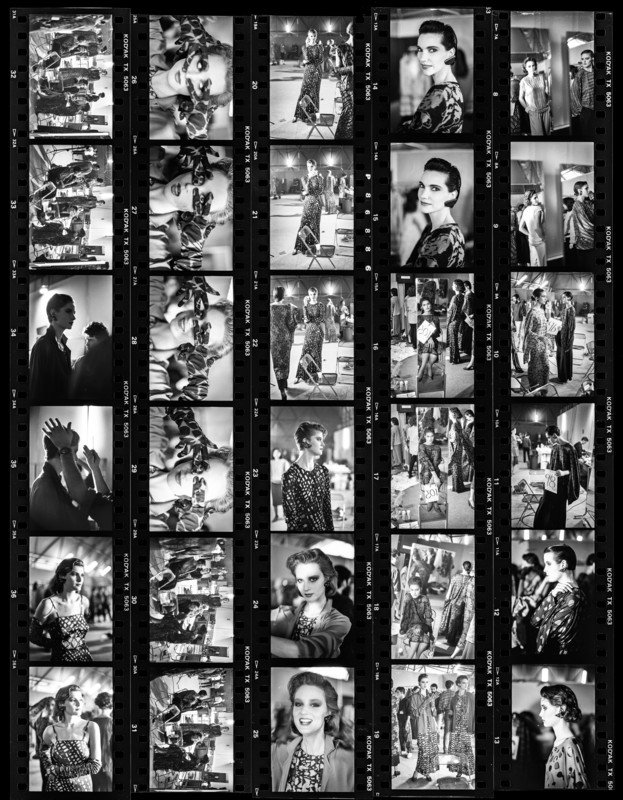

There were no other photographers backstage. I loved it. The models opened up and let me come close. It was the perfect place to do my portraits. I felt the film, frame-by-frame, wind through my camera. I felt my lens caress the skin. I worked with one camera and one lens without flash. I blended in. There is a raw and sensual energy backstage. A feeling happens when the pounding of the music mixes with the physical movement of the models. The girls are transformed into archetypal women. There is an intoxicating thrill of being close to the model when she looks in the mirror and I see into her eyes. I react instinctively. The flash of skin and the wild hair seduce me. I lose equilibrium. Often I am overwhelmed, overstimulated and I cannot work. It is like an opulent, out of control, pulsating, mess. But always, just when I pack my bag, I look up and, out of the mess, I see the goddess, beauty I see my picture. It is an instinctual and physical-like connection. The moment I saw the developed film I was pulled into a new universe. The atmosphere of the room, with the strong lights and the deep space backgrounds, transformed the models into actresses and created a world of cinema that I hadn’t seen. I learned this from Helmut: “The way a picture comes out is not necessarily the way one sees it with the eye. The camera takes in more information and the photograph interprets the world.” I thought of the film 8 1/2, by Federico Fellini, where he edited in still photographic portraits as a way to break up the action.

An actor would appear in a scene, stop talking and look right into the lens of the camera. The still photograph opened up an alternate universe.I worked on this project in Milan, Rome, and Paris. I photographed Armani, Moschino, Valentino, and Mugler. I put together the pictures and showed them to the magazines. I believed they would make a very beautiful reportage story. A few were published in Italian Vogue, but most of the art directors turned me down, for them, there were not enough dresses. In 1985, I was able to get a meeting with Carrie Donovan of The New York Times. I sat in her dark office on 43rd Street watching as she examined my portraits and backstage pictures. I was nervous. After some time she rose, and peering at me through her huge black-rimmed glasses, said, “I love these, these are cinema verité!” She assigned me twelve pages and a cover for Fashion of the Times. I moved to New York and worked for Harper’s Bazaar, GQ, Rolling Stone, and advertising agencies. I shot all day and edited all night.

Many of my friends from Milan moved to New York and we met and partied at the Mudd Club or Area until dawn. There was a lot of drinking, a lot of cocaine. One model told me she would stay up all night and in the morning hours go do her Vogue cover shoot. It was crazy and wonderful. In 2002, I had a strong desire to see a more realistic image of a model. I thought about my portraits. I thought about movement. I wanted to be close to the model engaged in a real-life situation. Once again, I needed the backstage. The fashion shows had become chaotic. Getting access was difficult and security was very, very strict. There was new aggression in the air and security guards at every door asking to see your pass.

The Internet created an endless and voracious appetite for images. It was about quantity. There was intense competition as dozens of photographers, video crews, and journalists competed for material to feed the online fashion sites. Thankfully, a good friend of mine, Don Ashby, got me access and I was able to do my pictures at the shows in New York, Paris, and Milan: Alexander McQueen, John Galliano, Helmut Lang, Prada, Saint Laurent, Balenciaga, Lanvin, and Karl Lagerfeld. I was fortunate to photograph the top models and fashion of the time.

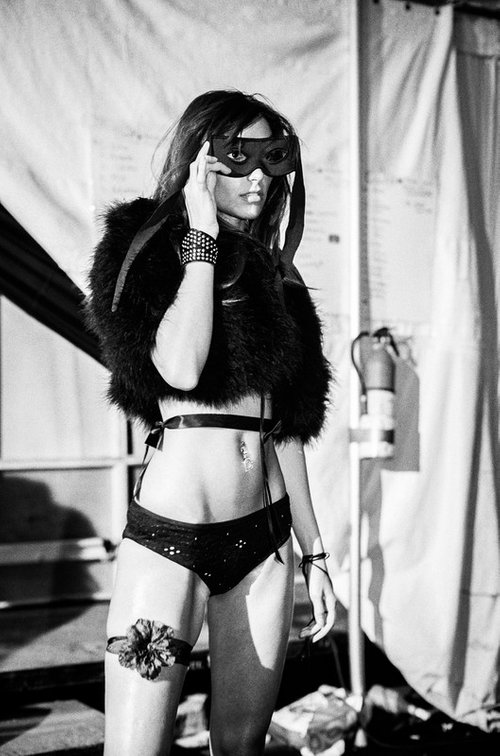

The new pictures had direct and nervous energy that I liked. I started using a small flash, just enough to light up the eyes. It gave the pictures a raw beauty. I realized I was drawn to certain models over and over: Karen Elson, Lisa Cant, Anne V, and Guinevere Van Seenus. There was a quality about them that I loved. I would patiently wait to photograph them, looking for just the right moment to approach. Often I had only a few seconds. “Hi Lisa, you look beautiful, can I take a photo, wonderful fabulous, got it, thank you, lovely.” I learned to be invisible and slip into the narrow space between the model and the makeup artist. Many times I had only ten inches of space to work. I was face to face with the models while they endured the process of beauty. I looked closely at the eyelash curler and the prongs of the mascara brush. I watched as the experienced hands of the hair stylists pulled, twisted, and sculpted the hair. I instinctively understood the hierarchy of modelling and waited for certain expressions of strength or vulnerability.

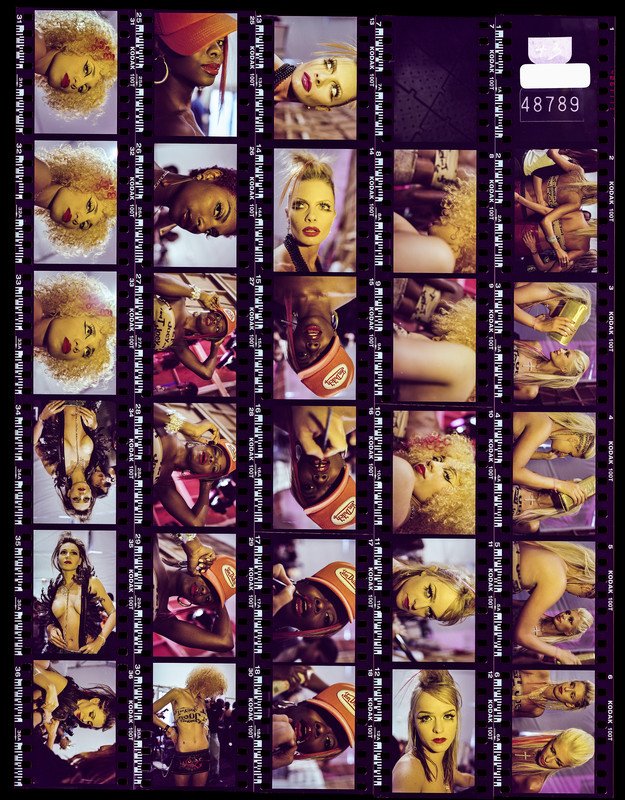

I showed the beauty and joy, but I felt it my responsibility as a photographer to show the realities as well. I started to work the shows where I live, in Los Angeles. No one from the fashion world of New York or Paris came to the shows in LA. The big models refused to do this work. The talent was local and there was a raw quality that was more street, and I liked it. Security was relaxed and there was a willingness in the air. There were crazy colored lights, overdone makeup, and teased bleached out hair. The spray-painted models in their fishnet stockings reminded me of the Showgirls of Reno. The swimsuit shows, with the colorful halter-tops, body paint and skin sent me right back to San Francisco in the 60s and the psychedelic world of the Fillmore West. I thought about my mother in her red lipstick and designer dresses. I thought about freedom of expression and the talented people that work to make this fascinating world come to life.

I realized how much I love the world behind the curtain, the world of the backstage. I am not sure why these pictures, over 500 rolls of film, remained in my archive, unseen, for so long. I loved the pictures and spent many hours in the darkroom making prints. Last year I moved into a 1920s photo studio in Venice, California. There, I found myself face to face with years and years of my work, stacked up in worn-out file boxes. One day these cardboard containers overwhelmed me. They appeared as vessels, and hidden within were these archetypal images. I opened the boxes and spread out all the negatives and contact sheets on my table. I rediscovered the portraits. Everything was still there, the models, the light, the movement, and the intimacy. The rich colors and tones of the analogue film, combined with the beauty of the women, were timeless. I knew I must make this book.

Just Loomis, Los Angeles

click to view the complete set of images in the archive