Disability & Armed Conflict

© Giles DuleyThere is no truth in photography, just honesty. No single image can tell a full story or give you a complete insight into a person’s character. We as photographers simply attempt to catch a fleeting moment, a fraction of light that gives momentary insight into another life.

A project as complex and nuanced as this means I could never tell the whole story. Every person has their own opinion on how we should represent those with disabilities and in my mind that thinking is dangerous as we stop seeing people as individuals. There is no ‘right’ way to tell a story, no single narrative in portraying the experience of somebody living with a disability. Reality is not black and white.

This project is intensely personal to me. I don't often refer to it but I too am living with a severe disability. In documenting those affected by war, my life became intertwined with theirs when I lost three limbs to a landmine. The price I paid for doing my work was huge, but the gift I received in return, it’s equal – I understand these stories in a way no other photographer could.

Some days I feel unstoppable and that I have overcome the barriers that injury has placed in front of me. Some days I feel weak, I sit and cry thinking I’m not strong enough. Who am I? I am stubborn, I am strong, I am unbreakable, I am difficult, I am vulnerable, I am weak, I’m scared, I’m angry, I’m grateful, I’m normally happy but at times, I’m not. That's is who we are - living with a disability means we are neither hero nor victim; we should not be pitied nor put on a pedestal. We are you. We are like every other human; complex, contradictory and wonderfully unique and all we ask is to be seen that way.

These photographs and stories give you a glimpse into the lives of others. I would hope they do so with an honesty and insight you don't always get to see. The good, the bad, the laughter, the tears; life as it is.

No one person should face a disadvantage because of race, culture, religion, sexual orientation or disability. No person should face a life of prejudice because of an injury or lose their human rights due to their disability. In all these conversations it can no longer be about us and them; it is simply about us. And we will only move forward when we move as one.

click to view the complete set of images in the archive

John Ayume, 62, had his leg amputated in 2012 as a result of cancer. When shootings started during the night in his village in South Sudan, John and his wife had to quickly flee. John took his crutches but in the rush had to leave his prosthesis behind. Without his prosthesis, John has grown frustrated.

John Ayume, 62, had his leg amputated in 2012 as a result of cancer. When shootings started during the night in his village in South Sudan, John and his wife had to quickly flee. John took his crutches but in the rush had to leave his prosthesis behind. Without his prosthesis, John has grown frustrated.“We are not disabled if we are able. If I had my leg, I would be able.” That has not stopped him from being an active figure in the community. John works in the camp as a volunteer. He travels around the camp, identifying vulnerable people and people with disabilities, and helps them access support.

For Catarina Kade, 70, life in South Sudan was good. Her friends and family lived close, there was plenty of food, and the paths and roads were smooth so she could get around in her wheelchair.

For Catarina Kade, 70, life in South Sudan was good. Her friends and family lived close, there was plenty of food, and the paths and roads were smooth so she could get around in her wheelchair.Then the war came to Catarina’s village and they started to slaughter her community. Her family helped her as best they could, but as they fled Catarina had to leave her wheelchair behind due to the rough terrain. So for the journey to Uganda, which took a week, she had to rely on a crutch.

Catarina now feels lonely in the camp. It is very rocky and she cannot move easily. She wishes she could go to have a chat with her neighbours but spends most of her day alone in the shade of her hut.

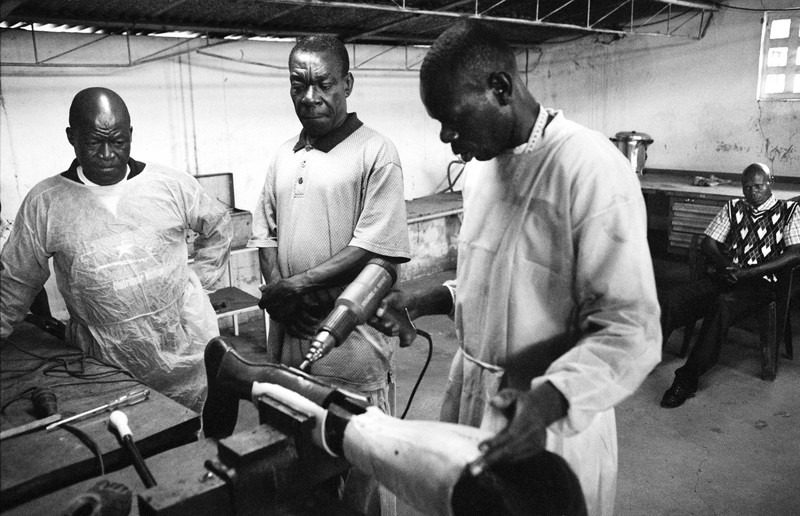

Sapalo was playing in his uncle’s house when he saw a large rat dash across the room. He looked for something to hit it with, grabbing a lump of rusting metal that was sat on the table. He threw it at the rat. A bright heat engulfed him and he was thrown to the floor. Disorientated he tried to get up, but he couldn’t. Unknown to him, the lump of metal he’d picked up had been the explosive warhead from an RPG (Rocket Propelled Grenade) that his uncle had found and brought back to the house with the intention of safely destroying it. Its blast destroyed both of Sapalo’s legs. Later that day they would be amputated just below the knee.

Sapalo was playing in his uncle’s house when he saw a large rat dash across the room. He looked for something to hit it with, grabbing a lump of rusting metal that was sat on the table. He threw it at the rat. A bright heat engulfed him and he was thrown to the floor. Disorientated he tried to get up, but he couldn’t. Unknown to him, the lump of metal he’d picked up had been the explosive warhead from an RPG (Rocket Propelled Grenade) that his uncle had found and brought back to the house with the intention of safely destroying it. Its blast destroyed both of Sapalo’s legs. Later that day they would be amputated just below the knee.

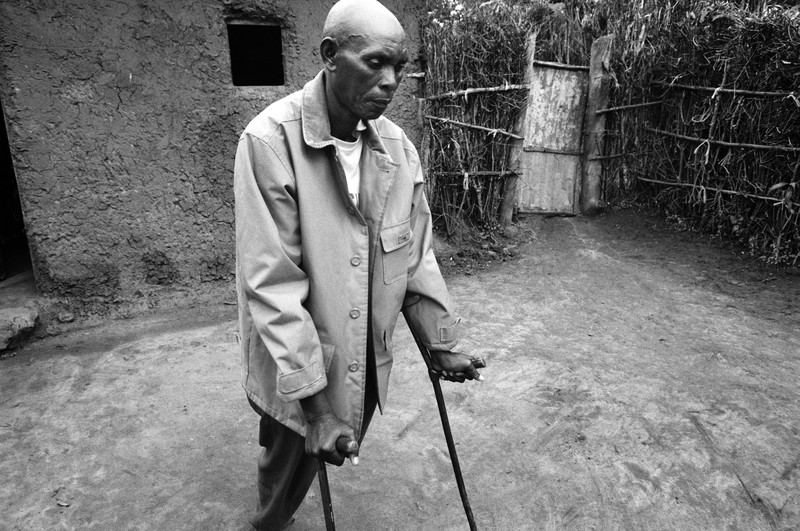

Innocent Karangwa, 60, is one of the thousands of people to lose limbs during the Rwandan Genocide.

Innocent Karangwa, 60, is one of the thousands of people to lose limbs during the Rwandan Genocide.He has struggled to work since his injury. He has been diagnosed with PTSD but has been offered no support, as a result, he is unable to access work and his local community. He remains isolated. In his own words, he feels ‘abandoned’.

“My whole life has been affected by war. I have to do everything; it just takes me more time and is more difficult. I will survive for my family.”

Since his accident, Vanthy has married and has six children. While his wife works, he cares for the children.

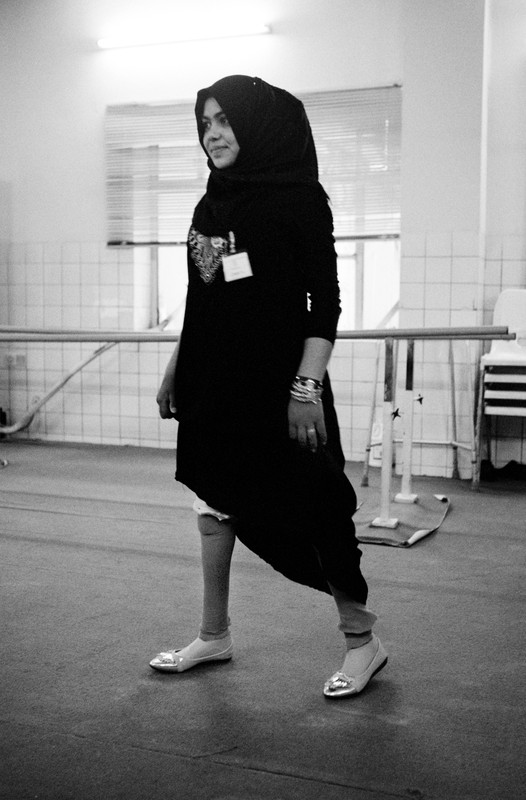

Now 16 she regularly has to visit EMERGENCY’s Rehabilitation Centre for a new prosthesis. One of the challenges for children growing with limb loss is the constant need to refit the socket as the child grows.

Sulaimaniya – March 2017

Kholoud. Lebanon and Holland. 2014 - 2019

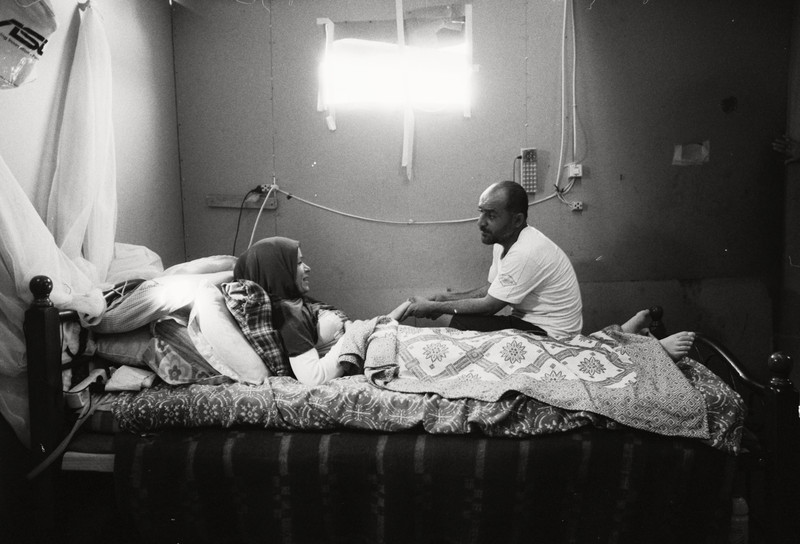

Kholoud. Lebanon and Holland. 2014 - 2019In 2013 Kholoud, 35, was working in her garden in Mo’damiyat al sham with her children when a sniper shot her through the spine. She collapsed, paralysed from the neck down. “I tried to plant a small area of land near our house as it wasn’t possible to get vegetables like before,” she said. “I was taking care of the plants with my four children and suddenly a bullet hit my neck and I fell down and lost sensation. I could not move any more.”

After her initial treatment, her family managed to get her out of Syria Eventually they found themselves living in an informal tented settlement in Lebanon’s Bekaa valley, one of the thousands of unofficial camps dotted across the country.

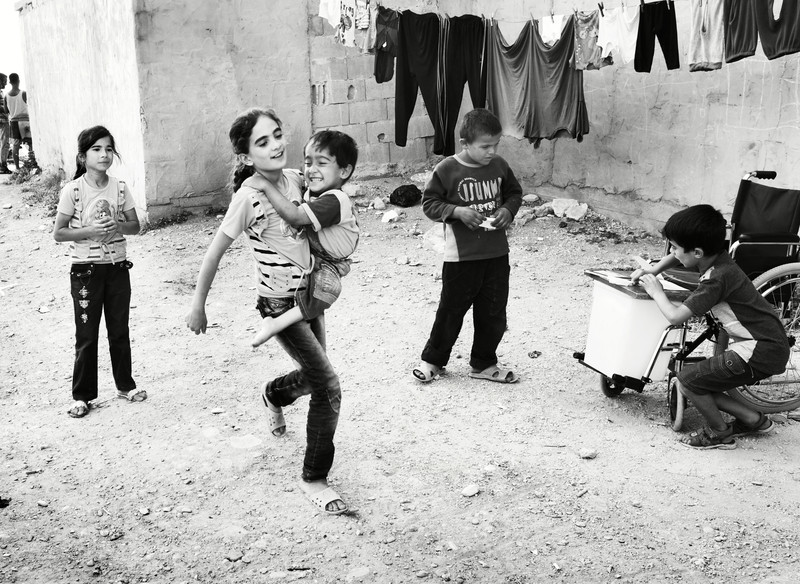

After their house in Idlib, Syria, was destroyed in 2012, Aya and her family fled to Lebanon where for two years they lived in a makeshift tent next to a cement factory. As a result, the children suffered from breathing problems. Eventually, they were moved by a local NGO to an unfinished building on the outskirts of Tripoli.

After their house in Idlib, Syria, was destroyed in 2012, Aya and her family fled to Lebanon where for two years they lived in a makeshift tent next to a cement factory. As a result, the children suffered from breathing problems. Eventually, they were moved by a local NGO to an unfinished building on the outskirts of Tripoli.Aya, 7, has spina bifida, and without access to medical support and suitable living conditions, her life in Tripoli was constantly under threat. The family waited in limbo. Despite her unbreakable spirit and resilience, Aya’s health deteriorated.