HERERO

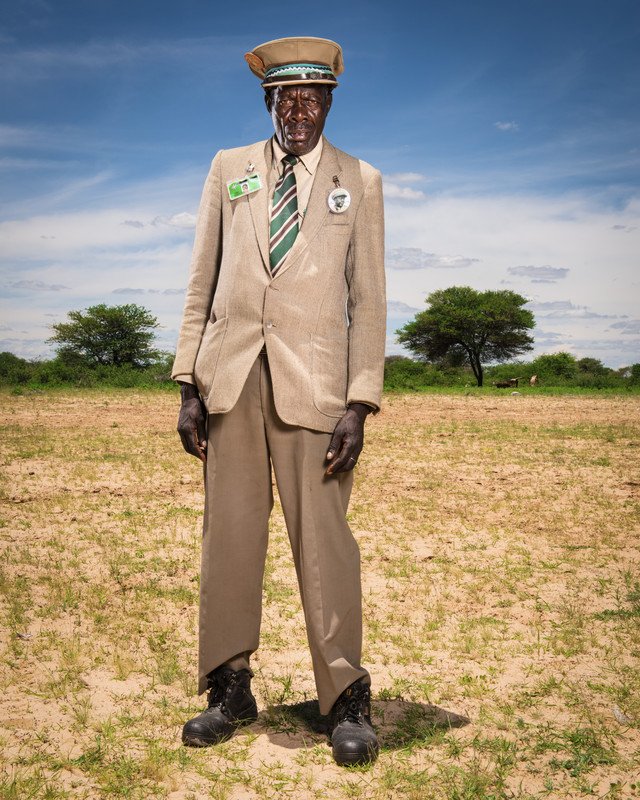

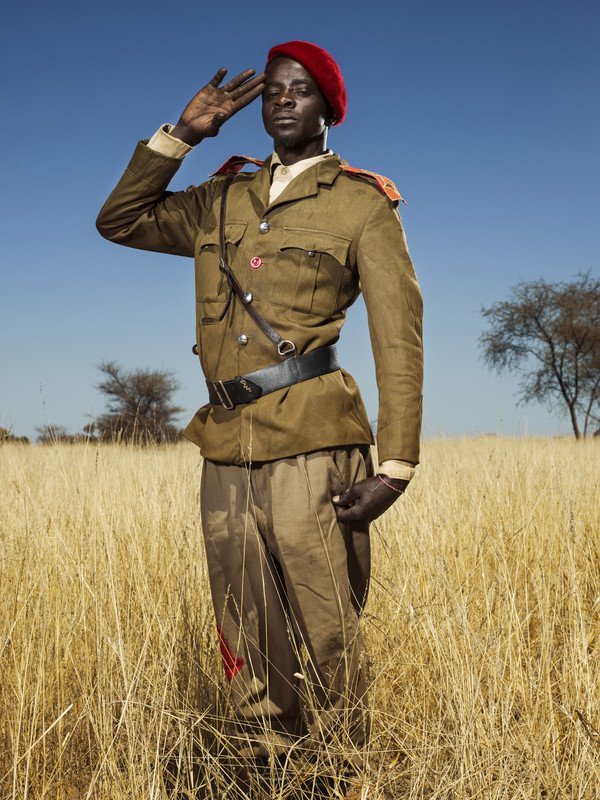

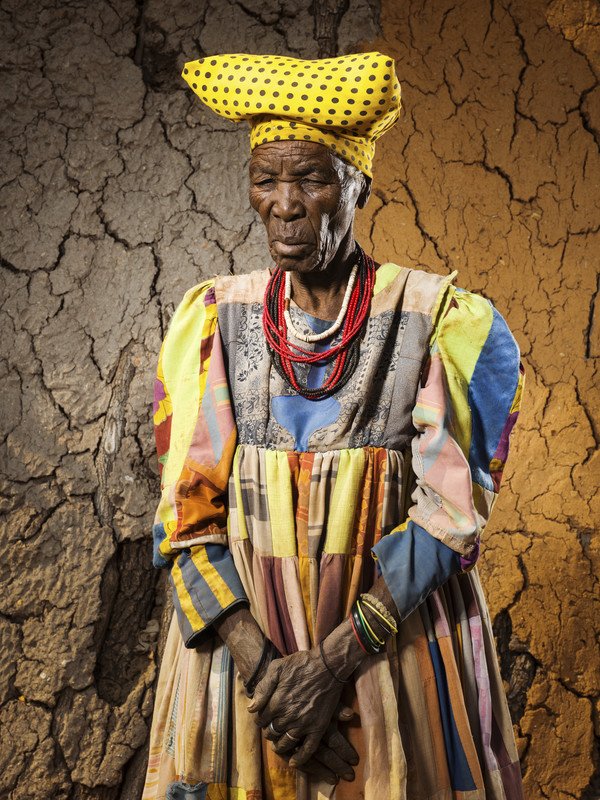

© Stephan GladieuIn the Herero series Stephan Gladieu made in Namibia, he questioned the identity renaissance of the Hereros through the conspicuous and collective wearing of the clothes of the German genocidal ancestors. During colonization at the beginning of the 20th century, the Germans in fact exterminated 80% of the Herero population.

Today, like hunters who wore the skin of their trophies, the Hereros have adopted the costume of German soldiers, the executioners of their people. Women, on the other hand, wrap themselves in Victorian dresses, the same ones that their enslaved ancestors were forced to wear, but revisited in local and multicolored fabric.

“My series of portraits captures a generation that did not experience the genocide, but today bears the transgenerational identity root. Their identity is written in a collective memory of appearance and expresses their determination to forever link their identity to this genocide. Thus, their appearance is an act of memory: it freezes time so as not to let it erase the crimes. Substance of an identity renaissance that also reveals the choice of a voluntary and conscious disappearance of the individual, of their singular identity and their own history, to dissolve in the plurality of a more powerful memorial collective.”

Memory of a Genocide.

In Namibia, on the trail of the first genocide of the 20th century.

Between 1904 and 1908, the German imperial army deported and massacred tens of thousands of Hereros on a territory that would become Namibia. Are the descendants of the victims still victims? On site, after more than a century and two world wars, time has not closed the wound of an ignored genocide.

On May 12, 1883, the German flag was hoisted for the first time in the sky of southwestern Africa. "Deutsch-Sudwest Afrika", as it was called until 1915, is now known as Namibia. Nostalgic postcards of a promised Eldorado that was supposed to become Germany's California can still be found in the shops of Windhoek. These are remnants of the ambition of a Kaiser who, following the example of France or Great Britain, dreamed of a colonial empire. It is a sepia-colored memory of a fantasized Reich that still erases the dawn of October 3, 1904. On that morning, on the hill of Osombo zoWindimbe, General Lothar von Trotha read to his exhausted troops the extermination order he had written the previous evening: "Inside the German territory, every Herero, armed or unarmed, with or without a herd, will be executed. No woman, no child, will be allowed on the territory: they will be brought back to their people or shot. These are the last words that I address to the Herero nation, myself, the great General of the all-powerful Emperor of Germany." As a signature, he had two prisoners lynched.

The German conquest proved more complex than anticipated. The Hereros represented 80% of the population. As nomadic herders, they dominated the economy and formed the most powerful army in the region. In addition to their determination, young Germans launched into an improbable conquest in the middle of the desert faced diseases and exhaustion. Nevertheless, more than 65,000 Hereros would perish. They were murdered, hanged, pushed into the furnace of the Kalahari, deported to labor camps, and decimated by diseases. In addition to the Herero victims, there were also Namas, and probably San people whose numbers were never counted. Bodies were sent to German universities, dismembered by their own parents under the threat of arms. There, they were studied by professors whose racial theories would nourish the germ of Nazi ideology.

Bruised, humiliated, and entrenched in the country's most arid lands, the Herero people survived. Their martyrdom has been passed down through the generations, sometimes embellished with legends. Today, like the Namas, they are demanding reparations from Germany for this little-known crime against humanity, the first genocide of the 20th century.

About an hour's drive from Otjinene, the hill of Osombo zoWindimbe appears so isolated that very few Namibians know where it is on the map. Every year in October, between five and nine thousand Hereros gather at the place where Von Trotha ordered their extermination. Since 2008, Osombo zoWindimbe has officially become a historical park (Ozombu Zovindimba Cultural Center). Ukaurua Kangumini, a young man who lives nearby, remembers that bones were found in the soil when the modest monument's foundations were dug. Places of memory are rare in Namibia. In the capital, there is nothing to indicate that the national museum rests on the ruins of a fort that served as a concentration camp, while the train station was built on a mass grave. In the south, near Luderitz, the Shark Island camp where about 3,000 prisoners died has become a campsite.

To retrace the topography of the massacre, one must follow the Hereros themselves. Let oneself be guided in desolate corners, listen to words that revive the past. In Otijinene, everyone knows the Ngauzepo tree. Pictures taken by German soldiers testify to its sinister function under the occupation. Fleeing to Botswana, several dozen Hereros were hanged from branches still marked by the marks of the ropes. Some say that the spirits could be heard screaming until the 1970s. Due to a lack of resources, the Hereros do not engrave their testimonies in marble. Each person becomes the guardian of the memory of their own: "In the history books of the school curriculum, the genocide does not go beyond two paragraphs," notes Ester Muijangue, president of the "Ovaherero/Ovabanderu Genocide Foundation," which carries the Herero cause throughout the world. "In Africa," she continues, "political parties represent tribes. However, because of the genocide, we are no longer the majority. In terms of numbers, we are only fourth in the country. It is therefore difficult to be heard." Retired mathematics professor Ehrenfried Ndjoze receives visitors in his garden, on the heights of Talismanis: "Traditionally, it is not in the school benches but on the occasion of festivals and other rituals that the past is transmitted," he confirms. History is mainly displayed in clothing. After the war, men adopted a uniform that evokes... that of the German soldiers! Cap, khaki jacket, stripes, and belt. Women, on the other hand, wear dresses with wide ruffles, whose pattern is based on Victorian fashion. "Sometimes people ask me why we wear the uniform of our executioners," says Ester Muijangue. "In the African context, the hunter wears the skin of the beast he has killed. Similarly, the soldier takes the enemy's uniform. It is proof of his victory. After the genocide, the uniform and the dress became our identity." Women often sew their own dresses. Men who cannot afford the outfit do their best to make a green or khaki shirt. Mirror fragments sometimes serve as medals, a fork and spoon can adorn the belt.

"They introduce themselves by announcing ranks: commander, lieutenant... to salute, they puff out their chests and stand at attention. At the sound of a whistle, they sometimes parade in step through the streets. Yet they do not form an army. Their procession is a dance, their uniform a costume. Thus tradition has frozen the course of time and with it the people's pain. Because their martyrdom is also their pride. In Otjinene, Vetarera Katjizeu struggles to contain his large frame in his uniform. For years, he cleaned ferries that sailed across the English Channel, "and worked at every job that an African works in Europe," he says. "We were physically massacred, but also spiritually. In the past, we had African names, our religion, our costumes. Now, we wear this uniform precisely because it is not ours. We took it, it is a sign of our resistance. A small people of African herders, we rose up against a Western empire. A country so strong that it would only be defeated by a global alliance in 1914 and 1939. Don't forget: in the twentieth century, the Herero were the first to fight the Germans."

The brutality of the past is also tattooed on the faces of their descendants. In every village, there are still mixed features. Light skin, straight noses, all traces of the rapes committed by the occupier. Away from Otjinene, Angela lives in a crooked house set in a cactus garden. At 98, her skin is almost pale, and her hand fragile as a bouquet of twigs: "my mother was a cook, my father a farmer on a German farm. One day he had to go away for a few weeks. When he came back, my mother was pregnant. I was born as white as you see me. What happened in the kitchen? It's not hard to guess. I was called Angela in German and Inaakihe, which means "the child of the kitchen" in Ojiherero." At the end of her life, she concludes that her best memories will remain of good meals shared with family. "I especially love desserts. Actually, I love everything that's sweet," she says as if her fate was entirely marked by the kitchen.

At the end of the genocide and the colony, the rapes persisted. In Okakarara, a northern town bordered by a surprising number of hair salons, Nemonuinjo Kaangundue recounts the sufferings of her family: "My grandmother worked for a certain Howard. He raped her. That's how my father was born. In those days, the Herero killed babies conceived by rape. Immediately after his birth, my grandmother had to flee with my father in her arms. Until he grew up, she blackened him every day with stone powder and cow dung. Once he was a child, he was saved, the adults could no longer kill him. The other kids teased the mixed-race kids but they were accepted because the Herero are perpetuated through the mother and not the father." On her lap, her grandson, wearing a Captain America t-shirt, listens distractedly to his great-grandfather's story. Sometimes, the pain resurfaces less in the eyes of others than in the mirror. "I hate my face," Willy confides. "My light skin makes me sick. Even my own son only has black eyes. I was born in 1952, my grandfather was a German whom I never met. I was named Wilhem under the pretext that whites do not remember Herero names.

"I hate my first name. I introduce myself as Willy, but I identify with my Herero name, Kahehura, which means 'I will never be a slave'. I was baptized and I learned to hate the Church. To me, the Germans had everything planned out. First, priests came to brainwash us, talk to us about love and tolerance. In reality, they were preparing the ground so that the soldiers could more easily massacre us. Finally, farmers arrived to exploit our land. The goal of colonization was simply the theft of our land." Mrs. Kaangundue continues, "We are not at home here. I consider this place a reserve. The shrubs poison our cows. There is no water. We all hope to return one day, to regain the country that the Germans deprived us of." These words echo the refrain sometimes repeated by Herero women: "Ndundu kenjikotore himbahene Kaondeka ka tongua," bring us back to Kaondeka, the mountain range now known by the German name Waterberg."

The Earth Namibia's history has a particular feature: independence did not lead to the departure of the colonizers. Their descendants make up the white Namibian community that exploits lands conquered over a century ago. Along the Waterberg, 113 years after the historic battle between Lothar von Trotha's troops and Herero commander Samuel Maharero's forces, walls and barbed wire shelter prosperous farms. A few kilometers away, Herero villages are often without electricity. Water is sometimes collected in drums placed under tin roofs. Some try to organize, like Kaekurupa Rukero. Afflicted with AIDS, he has let his wife try her luck in Canada. He remains on site, in the Otijinene region, desperately seeking ways to develop an irrigation system in his village to cultivate his "Garden of Hope," a shared vegetable garden. The fires of the past fuel the frustration of a condemned present.

Poverty is seen as the consequence of a too-forgotten genocide. Chief of the Hereros of Okakarara, Ripeua Kaangundue indignantly says, "the Germans had no cows on their boats when they arrived. This means that the ones they raise today are ours! I respect the law that protects property rights, I would not encourage young people who are seriously considering occupying lands by force, but I would not oppose it. My deep conviction is that the Germans must leave." Others are more measured or pessimistic. "We all talk about going home someday, but deep down, everyone knows we're going to stay here," sighs Rinoumba Alfons Kahuure, a 39-year-old livestock farmer in Talismanis. What was destroyed in the last century will never be repaired. The Hereros will not become the majority population of Namibia again. What can be done, however, is to improve their living conditions."

In 2011, Germany returned twenty Herero and Nama skulls to Namibia. In 2015, it acknowledged that the crimes committed between 1904 and 1908 were a "genocide." Last March 16th, a New York judge decided to follow up on the complaint filed in January by Herero and Nama representatives. In June 2021, Germany for the first time recognized that it had committed a genocide in Namibia, and it presented official apologies.

However, the 164,000 Hereros in Namibia are waiting for more than symbols. At this stage, they are also running into their own institutions. "The Namibian government would like all Namibians to benefit from these reparations," says former radio presenter Gotthardt Vanivi. "However, the only victims are the Hereros and Namas. In addition, those who fled the massacres must also be compensated, such as the Hereros in Botswana, Lesotho, or South Africa who do not have Namibian nationality. Every two weeks, we meet to assess the situation. Things are moving forward... but terribly slowly."

In Windhoek, Vekuii Rukoro, the supreme chief of the Hereros, receives visitors in a pleasant villa just a few steps away from Nelson Mandela Avenue. Armed guards monitor the house, and a buoy drifts on the surface of the pool. He offers visitors bottles of water with his image on them. Of all the Hereros, he is the only one who wears a red uniform. "Apologies have no value without material reparations," he insists, determined. "They will eventually come, and the Germans will have to stop playing ostrich and face us. In my youth, no one believed in independence. However, we have become a country. Similarly, in my opinion, the question is not if, but when the Hereros will regain their land. I remain cautiously optimistic. However, even when we obtain these reparations, we will always wear our uniform. It will remind us where we come from. This story will not be closed. We will never forget it." For Rukoro and his people, these efforts are not only aimed at reevaluating the price of history. Through other means, they are the continuation of a century-long struggle.

These meetings took place according to Herero tradition, under trees and on folding chairs. There was always a fire nearby, the fire of the ancestors that never goes out. The conversations were long, sometimes theatrical. There was anger, some tears, and a few smiles. And then there was this man, with his cane, neat mustache, and slightly crooked glasses: "I would like to understand why the Germans came here, why they left their families to go so far, to the end of the ocean, to kill us and conquer our land," he said simply. "Was there really no room left in Europe?"

-text © Adrien Gombeaud

click to view the complete set of images in the archive