Homo Detritus

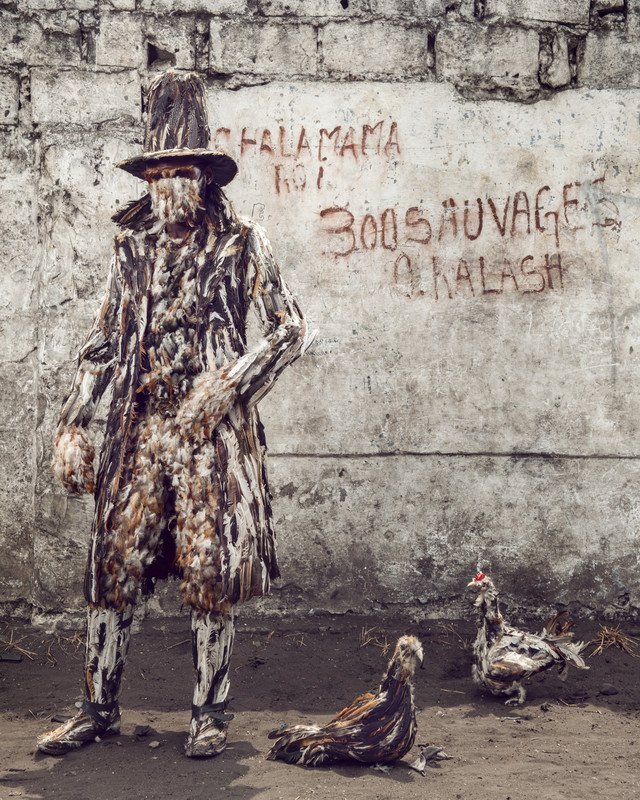

© Stephan GladieuOn the waste of Kinshasa

A recent study by the INRAE, a research institute for the environment alerts us to the worrying invasion of plastic. Since its appearance in 1950, plastic has conditioned all our daily life. And if at the time nobody was worried about the heap of waste, today humanity is totally addicted to it. Today 13 billion tons of plastic waste are scattered around the world. In 2050 it will be 50 billion tons.

This global problem primarily concerns the poor countries that are becoming the world's garbage cans because the rich countries that are at the origin of their production have them taken over by the poor countries that are becoming the planet's landfills.

The second largest country in Africa, the Democratic Republic of Congo has one of the richest subsoils in the world in gold, coltan, diamonds, cobalt, oil ... and yet remains the 8th poorest country on the planet.

The DRC is a geological scandal.

For decades, like many African countries, Congo Kinshasa has seen its wealth exploited by international companies - mainly Chinese - in a commercial process resembling a new "raw materials syndrome". The lack of commercial equity in the mining and oil sector, the country's increased dependence on China combined with massive corruption by successive governments since decolonization, prohibits any equitable redistribution of the product of natural resources.

The poverty rate affects nearly 65% of the population. Life expectancy at birth is only 48.7 years and the school enrollment rate is 55% for a population of which 60% are under 20 years old.

The Congolese are among the biggest losers of globalization. They very rarely benefit from manufactured products that draw on their country's resources. In general, these products reappear in Africa in the third or fourth generation; at best they are obsolete, but more often than not, they are only waste products from industrialized countries that prefer to relocate their treatment. Kinshasa's slums are very often built on land filled with tons of untreated waste.

"What is born of the earth returns to the earth," Euripides used to say... In the DRC, we have corrupted the virtuous circle by transforming a feeding ground into a garbage can.

Another paradox: from this waste that is burying the slums of Kinshasa has just been born an artistic movement that borrows a lot from the approach of Arte Povera, the protest movement of the consumer society at the end of the 1960s in Italy. It cries out its urgency to live and no longer survive in the garbage and injustice of the world.

Cell phones, plastic, corks, synthetic foam, inner tubes, fabrics, electric cables, syringes, capsule boxes, car parts, cans, everything is the raw material - and yet already industrialized! - to denounce the chaos in which the Congo is kept.

Covered with a full mask made from this garbage, a generation of artists rises up and federates in a collective that thirsts for a claim, a primary and visceral necessity to create and denounce.

If the Congo has partly lost its animist and mystical traditions, dissolved under the pressure of the Catholicism of the former Belgian colonists, these young artists are returning to the traditional source of the African mask. An inhabited mask, bearer of a spirit, a symbol of an overflow.

This collective is "Ndaku, life is beautiful", founded six years ago by the visual artist Eddy Ekete. Today it brings together nearly 25 artists, almost all trained at the Academy of Fine Arts in Kinshasa.

Painters, singers, visual artists and musicians, have united to denounce the tragedy of their daily lives, the wars that have resulted, the exploitation of women and men that results from it and ferments the unfathomable misery that deprives them of all dignity.

Originally, these artists had one thing in common: they had no resources, no support. Inhabitants of the slums, are naturally found in the garbage an abundant and free raw material. It was Eddy who created the first mask, paving the way for the young artists around him.

The collective welcomed me for two weeks to carry out this artistic project, which is a continuation of my work. I remained faithful to my photographic bias by choosing to make the portraits in the streets of Kinshasa, the setting and the character responding to each other.

The street is the common history of these artists. Their collective organizes street performances to raise awareness of the authorities and the inhabitants. It was, therefore, legitimate to place them in the reality of Kinshasa's ghettos.

All these photographs were taken with the written agreement of the collective and each artist. This work was done in total collaboration with them and I have therefore the authorization to diffuse and broadcast this series of portraits. I continue to support their work by promoting it to institutions and international cultural services.

It seems essential to me to recall that this problem of waste management and exploitation of raw materials is not limited to the Congo but concerns a large part of Sub-Saharan Africa, West Africa and Central Africa.

While some African countries are struggling to manage their waste, they are also recovering it from abroad.

Many industrialized countries send their waste to African countries, mainly because companies that use plastic in their products or packaging do not pay for recycling. In the U.S. and other countries, this has forced municipalities to bear the costs of collecting, transporting and processing plastic waste.

This burden remained "hidden for decades, mainly because about 70 per cent of this waste was exported to China," she continues. But in 2018, Beijing closed its doors to much of America's plastic, and some U.S. cities discovered they couldn't afford to recycle it. So they gave up on doing so.

Under the Basel Convention, which came into effect in 1992, countries cannot export their toxic waste without the consent of the recipients. This is why countries exporting end-of-life e-waste to Africa do so under the guise of a "charitable" donation: the objects transported are considered second-hand goods, in other words, second-hand electronic materials, which are, in turn, authorized. "In this sense, we find that the Basel Convention relieves France of its responsibility in its ability to find treatment solutions on its own territory," according to Nicolas Garnier, CEO of AMORCE, an association of local authorities specializing in waste management. He adds that this is due to the fact that "no one wants an electrical or residual waste treatment facility close to home".

As a result, the continent is flooded with waste. Uncontrolled landfills are appearing and several countries, including Ethiopia, Congo, Burkina Faso, Mozambique, Mali and Niger, see their dumpsites overflowing with household waste but also with toxic materials or electronic equipment from developed countries.

click to view the complete set of images in the archive

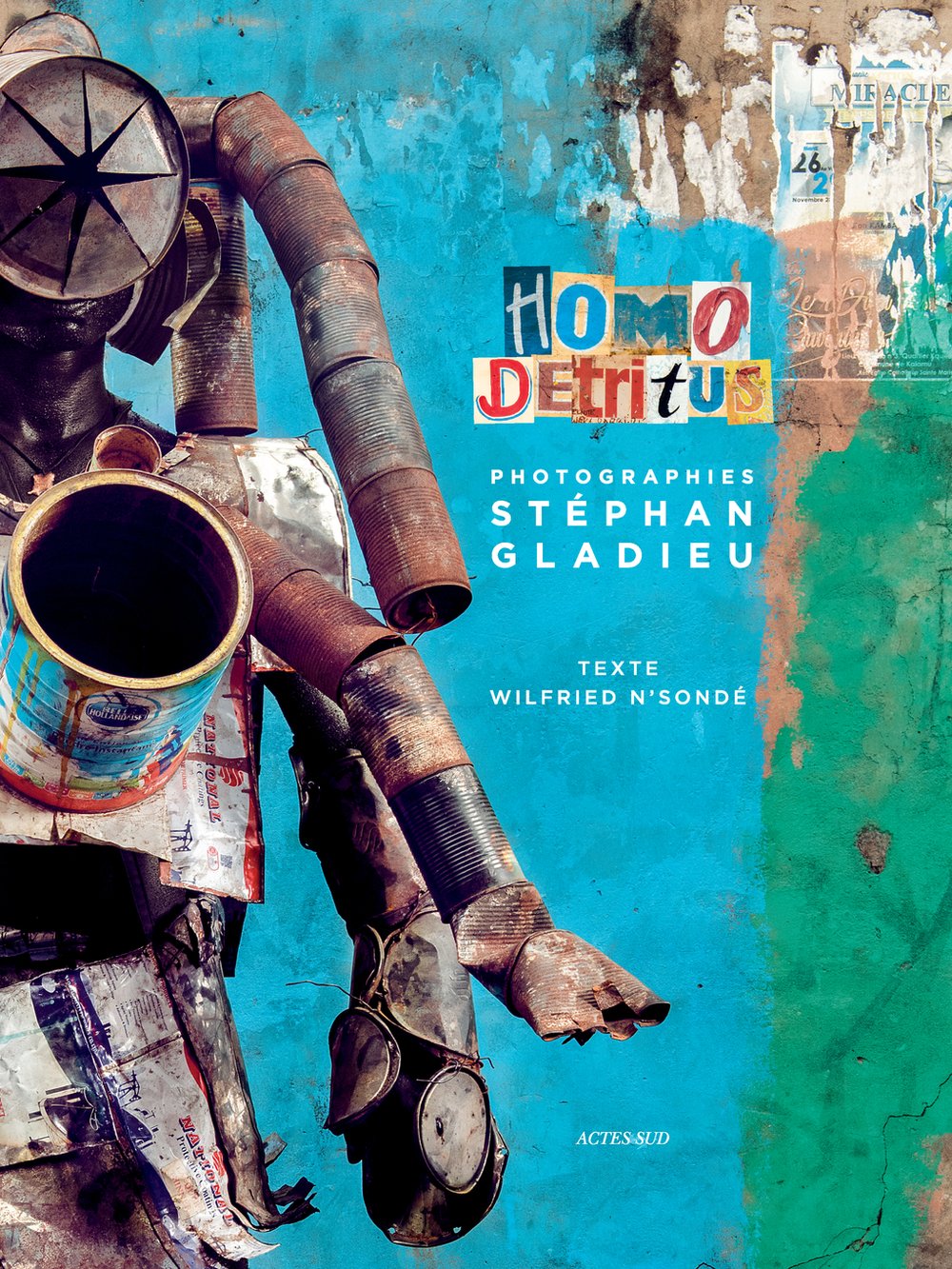

Publisher: Actes Sud

Publisher: Actes Sud September 2022

24.00 x 32.00 cm

104 pages

ISBN : 978-2-330-16748-6

Photographs © Stephan Gladieu

Text © Wilfried N'Sonde