How Do You Prepare For A School Shooting

photos © Lindsay Morristext © C.J. Chivers

The New York Times magazine commissioned the story and published it on July 3rd.

The New York Times magazine commissioned the story and published it on July 3rd.Some students remembered the unceasing screams of children calling for help, or the sight of peers wailing over seemingly lifeless friends. A parent recalled her rising discomfort over how realistic the artificial wounds and blood appeared to be. A fire chief marvelled that one student performed the role of a despondent teenager so well that she fooled him and three other first responders into thinking she needed real medical help, and left an emergency medical technician in tears.

On a Saturday in early June, less than two weeks after a shooting in a school in Uvalde, Texas, killed 19 students and two teachers, the village of Greenport, N.Y., a small coastal community on Long Island’s North Fork, held a regional exercise for first responders to sharpen their handling of a crime that in recent years has become common enough to enter crisis-response routine. The exercise at Greenport High School, which organizers said involved 62 simulated victims and roughly 240 first responders from multiple public-safety agencies and firefighting districts, was not directly related to the delayed and bungled handling of the shooting in Uvalde. It had been part of the local fire chiefs’ agenda since early January when First Assistant Chief Alain de Kerillis of the Greenport Fire Department proposed putting the simulation on the year’s training calendar. The world we live in now, he said, requires preparation so that departments will be logistically and psychologically ready. “Thirty years ago, back in the late ’80s and early ’90s, we just fought a fire and had a couple of beers afterwards and said, ‘Oh, this is great,’” de Kerillis said in an interview at the fire station in mid-June. “Something is really wrong with what’s going on. So how do you mentally prepare?”

Data on the frequency and scale of mass-shooting simulations at schools are scarce. School districts and public-safety agencies have held them at least since the murders of 27 people in the Sandy Hook Elementary School shootings in Newtown, Conn., in 2012. Using stress and a degree of realism, they build on the now-common — and often legally mandated — lockdown drills held in schools throughout the land, in which students and staff members practice quietly sheltering in classrooms or other parts of a school to limit exposure and reduce, at least in theory, the number of potential victims a shooter might access. The more detailed and dynamic simulations introduce more stress and confusion and can be used to train not students and staff but first responders. No industry or national standards exist for the drills, and their design, goals and techniques vary widely, at times including simulated active shooters carrying mock weapons or firing blanks — an element that, like mass-shooting simulations themselves, has faced criticism for the risk of traumatizing participants, children in particular.

The Greenport drill was not imposed on the school’s staff or student body. It relied on students who volunteered to participate and was held on a weekend rather than during school hours. The village of Greenport worked with Firehouse Training Plus, a private firm that helps departments enhance skills via refresher training and simulations, to stage the enactment of this recurring contemporary American horror. The firm’s founder, Chip Bancroft, a retired fire chief, says that effective drills require intensive planning, collaboration and outreach so no one mistakes them for real and that whatever public misgivings surround simulations, demand for them from school districts and public-safety organizations is rising. His company, he says, has more requests for them on Long Island than he can fulfil.

In designing the drill, Bancroft and his peers recognized the baked-in limits of local first-response capacity. In many areas of the United States, a mass shooting can almost instantly overwhelm trauma-care resources. Exurban jurisdictions often have few ambulances, a relatively small number of first responders and few-to-no nearby emergency rooms, blood products or hospital beds. Greenport is fortunate to have a fire station with ambulance service a few blocks from the tan-brick school buildings that house public-school students from prekindergarten through 12th grade, and a hospital with an emergency room a little more than a mile away. But the firefighters are volunteers, the ambulance service has two vehicles and the emergency room could not be expected to handle 62 patients. Within minutes, a mass shooting could create more severely wounded victims than could be carried or treated by Greenport providers alone.

Moreover, mass shootings are almost always a surprise. Unlike other perils that can stretch emergency- response resources — extreme weather, an advancing wildfire, a pandemic — there is typically no warning that would allow supervisors to marshal staff or stockpile equipment and supplies in the days or hours before victims are harmed. Multiple first-response providers would rush nearly simultaneously to a shooting, and coordination can quickly break down. Bancroft and the participating departments hoped the exercise would identify weaknesses and lead to improvements ahead of any real-life event.

The scenario Bancroft developed assumed a young man had opened fire on students and faculty as they sat in bleachers for a pep rally beside the football field. It also assumed the shooter then ran into the school, where police officers were to contain and stop him. In the drill itself, there was no simulated shooting in the bleachers; the students who volunteered to act as victims did not see a mock attack. Instead, two exercises essentially played out in parallel. Outside, beside the sports field, the simulation’s victims took positions on and near the stands, and firefighters and emergency medical technicians rushed to treat and evacuate them. Inside, police officers practised confronting a man playing the part of the antagonist.

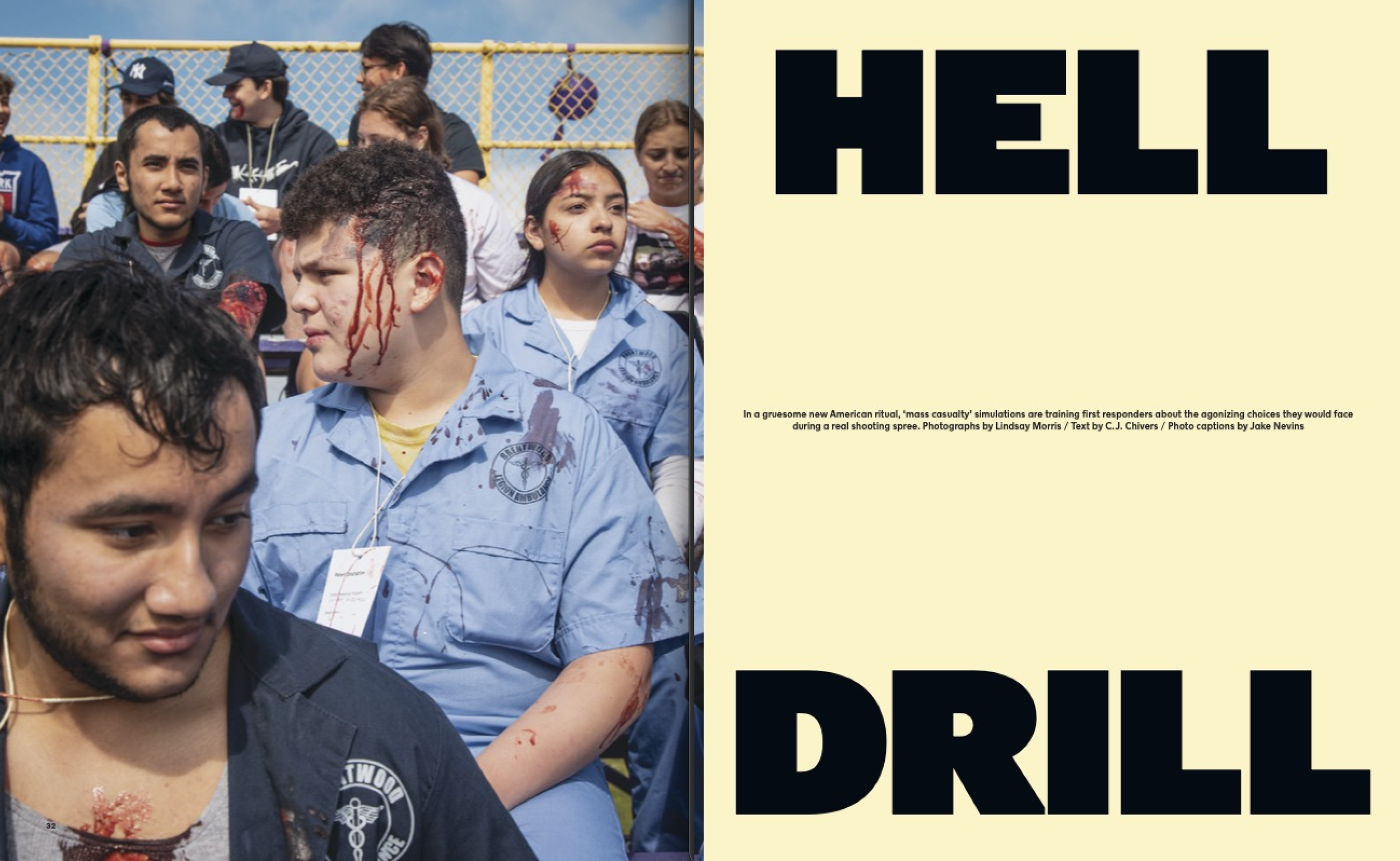

Even without a shooting being enacted, several participants said the drill had an unsettling feel, in part because Bancroft and other organizers outfitted the mock victims with fake gunshot wounds, doused them with artificial blood and assigned them roles to perform, including being in shock, emanating confusion or acting inconsolable, panicked or distraught. Four were assigned to pretend they were dead. To add stress and stretch resources further, smoke machines bellowed smoke in the nearby woods, a car was set afire and had to be extinguished and a medical-evacuation helicopter was summoned and landed beside the football field to simulate carrying critically wounded victims to Stony Brook University Hospital, roughly 50 miles away on roads often busy with traffic.

The volunteers, almost all of the high school students from Greenport or other districts in Suffolk County, gathered early to prepare. Among them was Diana Acevedo, 16, a junior at Bentwood High School who hopes to attend Columbia University and become a gastroenterologist. When organizers asked what role she would lie, Acevedo selected a bloody assignment. They affixed the latex likeness of a gunshot wound to her forehead and spattered her torso with fake blood. Thus adorned, and instructed to play dead, Acevedo spent much of the morning lying motionless on the grass. Though she knew it was a drill, she became uneasy as it began. The shots alarmed her. “One of my best friends, her name is Dayanna, she has really good acting skills and I heard her screaming: ‘Three of my friends are shot and no one is helping them! Please help them!’” Acevedo says. “When I heard these words I just imagined the little kids in Uvalde, Texas, shouting and seeing their friends dead. It hurt me deep inside.”

As first responders triaged the mock victims, one affixed a black tag to Acevedo, marking her as deceased and therefore a low priority for evacuation while rescuers worked on the living. Lying on her back in the sun, ants crawling over her arms, Acevedo heard her friend’s voice anew: “These are my friends! Why do they have black cards on their clothing?”

Her friend, Dayanna Roldan, also 16 and a junior at Brentwood, was notified of the exercise by the Brentwood Legion Ambulance service, where she and Acevedo are members of its first-responder mentorship program. At first, she was not interested. After the murders in Uvalde, she changed her mind. Roldan hopes to attend Stony Brook University and become an emergency-room nurse and felt a need for this type of training. “Unfortunately things like this happen,” she says, of mass shootings. “In order to prevent more casualties, you have to give a little more of your time.” When Roldan arrived at the field, she asked for a demanding role. “I volunteered to be hysterical,” she says, and so she spent the exercise shouting, running in bloodstained clothes through the crowds and even tugging and pulling on first responders, trying to drag them from treating the wounded to help the simulated dead. “I tried to make it as real as possible,” she says.

One firefighter, Second Assistant Chief Craig M. Johnson of the Greenport department, says performances like Roldan’s were disorienting. “The screaming, it hit us,” he says. “I had to backpedal just for a moment on that, to collect my thoughts, before proceeding. “The ominous feel fit the times. Just over a week later, a 15-year-old freshman at Greenport was arrested after threatening, the authorities said, to attack the school. The boy’s name was withheld to protect his privacy. After the arrest, the fire chiefs and Bancroft said their duties were ever more clear. “Our kids,” Bancroft said, “should have all the safety and protection we can afford.”

click to view the complete set of images in the archive