Infringement Of The Virtues

© Alexandre Silberman

“Men who have neither fire, nor place, nor attachment to profession, nor bond to the soil, arrive more easily than others to have neither faith nor law. They wander at random through the world, victims of the law of supply and demand, and they end up fatally in the major centres where disillusion and despair await them.”

— Abbot Lemire, founder of the « Ligue Française du Coin de Terre et du Foyer » (« French League of the Corner of Earth and the Home »). Parliamentary document of the session dated July 18, 1894

In a French society at the end of the 19th century, in the midst of industrialization, prey to the disintegration of its social and moral fabric, a major movement, notably composed of Christian democrats such as Abbé Lemire, promoted the allocation of plots of cultivable land to working-class families in order to give them back structure and dignity.

This was the birth of the workers gardening lots, which from its creation was endowed with ethical and political virtues.

The question of the well-being of the working classes is central, in response to the increasingly pervasive alienation that the economy and industry operate on them. Firstly by the resumption of contact with nature and its benefits. But also and above all by the reappropriation of one's labour-power, on one's own account and for one's own benefit: what is in one's field ends up at one's table.

If the aspect of moral order has somewhat disappeared with time, the workers gardening lots - gradually renamed « family gardens" - have lasted until today.

This is notably the case in the Seine-Saint-Denis area, which has the particularity of having successively hosted the largest market gardening plain in France, that of the Vertus (Virtues in English), and the largest industrial wasteland in Europe, the Saint-Denis plain.

It is from this first plain that the allotments of the Vertus take their name, under the protection of the Church of Notre-Dame-des-Vertus, which consecrated the miracle of the rain of 1336, saving the land that was then dry.

Located on the glacis of the Fort Aubervilliers, next to the family gardens of Pantin, they are a trace of the political as well as agricultural history of the territory.

The Vertus plain, which was built on former drained marshes, was sufficiently fertile and irrigated to be able to grow crops without water. A veritable breadbasket of Paris, the agricultural space began to be nibbled away in the 19th century by the establishment of unwanted factories within the walls of the capital, to the point of becoming mainly industrial.

It was in this context that the Vertus workers gardening lots were created in 1935.

Facing since 1956 the Courtillières housing blocks, one of the first large housing estates built in the Paris region, constitute a counterweight to the early urbanization of the area.

Having occupied more than 62,000 m2 of land in 1963, the gardens now only have 26,000 m2, divided into 85 plots ranging from 170 m2 to 500 m2. Already severely reduced in the 1970s by the extension of metro line 7, the creation of a regional parking lot and a bus station, its space is now threatened again by the development work launched in 2014 around the Fort Aubervilliers.

Aimed at revitalizing a neighbourhood plagued by social and economic difficulties, the ZAC (concerted development zone) of Fort Aubervilliers project calls for the construction of an eco- neighbourhood, a Grand Paris Express train station, as well as a swimming pool and its Spa/ Solarium extension.

Already started before the announcement of the victory of the Parisian candidature, these works are however since pushed by the prospect of the Olympic Games 2024, the swimming pool having to be used for the training of the swimmers engaged in the event.

First announced as only concomitant to their space, the gardeners of the Vertus learn in early 2020 that these projects encroach on it after the public authorities had until then assured that this would not be the case. In all, it is nearly 10 000 m2 of gardens that it is planned to raze, mainly to make way for the annexe of the Olympic swimming pool.

Postponed many times because of the health crisis, the construction site will finally begin in May 2021. And with it, it is a whole eco-system very specific in the urban environment which is threatened, in a city counting only 1,42 m2 of green space per inhabitant, one of the weakest figures of the French ground.

Although legally not owners, some of the gardeners, some of whom have been cultivating the land for decades, are screaming about expropriation, and are now resisting. In spite of the promises made by the State of compensation on other related lands, the anger does not weaken. Because it is more than a legal fight that is played here.

While France promises the greenest Olympic Games in history, putting forward new districts labelled sustainable development, two conceptions of ecology are confronting each other: the urban and technocratic one of modern developments whose enjoyment by all is promoted, against the agricultural and familial one of a community faithful to local heritage, in which the privative dimension of the places is inseparable from the notion of the common good.

“The gardens have kept many people here out of depression. ”

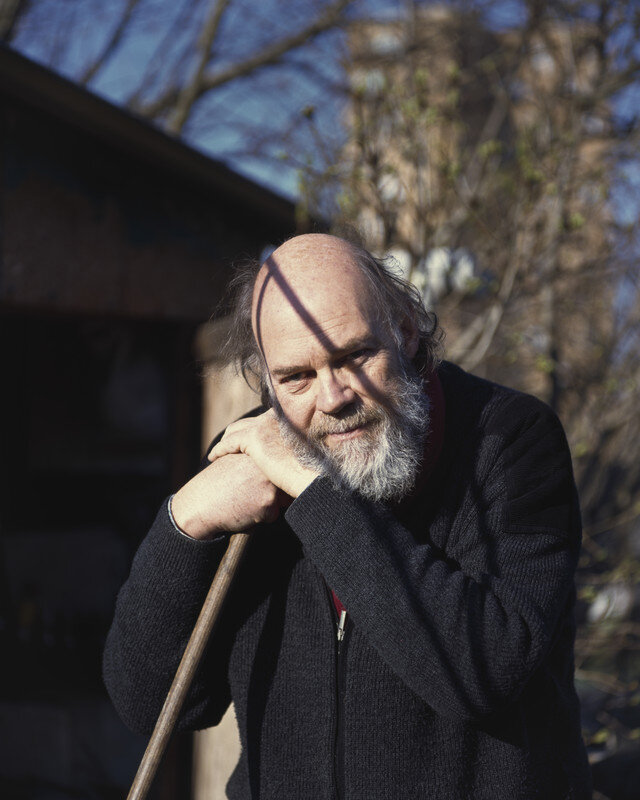

— Gérard Muller, vice-president of the Vertus workers gardening lots association.

A soil and its cultivations

If the cultivation of the soils of the former plain of the Vertus is part of the great tradition of this territory, it is no less plural and protean, linked to the migratory history of Aubervilliers and its department, Seine-Saint-Denis, the most cosmopolitan in France. And it is precisely through the work of the market gardeners that the flows were first made, as this required trade and a large workforce. The employees first came from nearby regions, such as the Bretons or the Belgians in the 18th and 19th centuries. With the arrival of industry came Italians, Portuguese, Spanish and North Africans. Aubervilliers is now one of the largest concentrations of the Chinese diaspora in France, which holds a large part of the 1500 wholesale stores in the city. In all, according to a 2019 study, there are 114 languages spoken there.

This mix can be found in the Vertus, where the sharing of the land is also a sharing of its crops. It is also, for many gardeners from immigrant backgrounds and often from rural areas, a way to reconnect with their heritage, working the soil to reclaim it. Covering it with concrete does not only mean destroying the cultivation effort that worked it, but also the cultural know-how that went through it.

A know-how that has sometimes been expressed over decades, like that of Eliane, the doyenne of the gardens, holder of inter-suburban agriculture prizes. It is this soil, which she still ploughs 48 years after her arrival, that allows her to eat today." If I lose my garden, I wouldn't take up another one. I have too many memories here, I wouldn't have time to make new ones," she says, even though her land is not threatened at this time.

In the gardens, the hand feeds the mind but also and above all the stomach. This is one of the roles required in order to have the right to occupy a plot of land: three-quarters of its surface must be dedicated to food culture. A salutary imperative in a city where 44% of households are below the poverty line.

“It is time to get a grip on ourselves and return to an existence better harmonized with the power and proper functioning of our organs. The concrete and material formula of this return to nature is the return to the earth, of which the allotment garden constitutes the most attractive, the most practical, and the most effective form of apostolate.”

— Dr Gustave Lancry, Annals of Public Health and Legal Medicine, 1905

The gardens are worker's not only because they were historically reserved for this class, but also because they put their manual force to work in order to reappropriate it. A political issue is at stake here, in which wage earners break the employee-employer dialectic to directly enjoy the fruit of their labour.

This is why many people here insist on keeping the original name of « workers gardening lots » and not the more modern name of « family gardens », less politically connected. While the working class itself is constantly disintegrating and has more and more difficulty in posing as an identifiable counter-power from a national point of view, the struggle that is taking place around the Vertus garden sometimes appears to be asynchronous, opposing two models of society from disparate periods.

This is because, despite their virtues, these gardens contain a fundamental inequality in their very foundation, which skews the balance of power. The farmers may work the land and recover the products, but the space does not belong to them: it is the possession of Grand Paris Aménagement (GPA), a state structure trading with the private sector. Thus, faced with the decision of the latter to recover part of the land, the gardeners were very quickly reduced to their status of simple occupants, far from the original will of Abbé Lemire to heal the structural inequalities of industrial capitalist society by reinforcing the feeling of possession among the dominated classes.

From this stems the incomprehension and the feeling of injustice among gardeners, more ideological than legal. Here and now, people have never seemed to be so dispossessed of themselves.

An irreplaceable anchorage

As soon as they learned of the plan to destroy part of the cultivated land, some gardeners began to mobilize, particularly around Gérard Muller, vice-president of the Vertus allotment garden association and one of the main spokespersons for the cause in the media when the matter began to make noise in the spring of 2021. While the current mayor argues that it is now impossible to go back, under a penalty of millions of euros in penalties, appeals are requested from the various stakeholders.

In their sights, the decision to build a solarium and spa complex concomitant to the Olympic pool. Although the latter would not in itself require the destruction of the gardens - its surface area would not cut into them - it is indeed the ancillary installations that would spread out over the currently cultivated land. An aberration for the gardeners, especially in view of a development project of the Fort Aubervilliers that wants to be eco-responsible, in the perspective of the 2024 Olympic Games declared as the greenest ever made.

However, the defenders of the cause refuse to position themselves as refractory to the modernization of the neighbourhood but instead want to find alternatives, proving that these major works are compatible with the gardens, as they had been announced before 2020. The architect Ivan Fouquet, one of the supporters of the growers, argues in particular that it would be possible to build this complex on the roof of the swimming pool, thus sparing the cultivated spaces.

While slogans are flourishing along with the plots, the public authorities still refuse to reverse their decision. Grand Paris Aménagement is offering another land, located next door, on a former soccer field that is currently fallow, as compensation. An indigestible offer for the most committed gardeners, who denounce the absurdity of announcing that they want to replace destroyed green spaces with an already existing green space.

The Zone

In 1841, Adolphe Tiers, President of the Council and Minister of Foreign Affairs at the time, launched the construction of the seventh and last Parisian enclosure to this day, in order to protect the city from external attacks. At the foot of these « fortifs", as they were called at the time, was a 250-meter wide strip of land consisting of the ditch, the counterscarp and the glacis. When the military role of the enclosure was abandoned in 1919, this non-constructible zone began to be occupied by the most precarious populations, and slums sprang up there.

Thus was born "the Zone" and it’s "zonards" who live there.

A few years later, it is on this glacis that the gardens of the Vertus are constituted. The popular soil is respected, and it will be cultivated through the ages.

High bastion of communism, Aubervilliers is integrated in 1968 in the new department of Seine-Saint-Denis, supposed to fragment a Francilian region red belt which had become too powerful.

The Courtillières district, a symbol of this double anchorage, both agricultural and working-class, sprang up in the background of the crops. Taking its name from the courtils, the small gardens adjoining the peasant houses, it is one of the first large housing estates built in the Paris region. Designed by the architect Emilie Aillaud and built in 1954, it is composed of a serpentine building of 1 kilometre long, 2 low buildings and 9 towers of 13 floors. Recognized as architectural heritage of the 20th century, it is now the subject of an urban renewal plan.

Particular attention from the public authorities contrasts with the fate reserved for gardens. While this historic city of the left has just passed to the right for the first time since the end of the Second World War, the ideological heritage of Aubervilliers has never seemed so contested. Like these sheds with their sometimes rudimentary structure, made of sheet metal and wooden planks, and which seem so fragile in the face of the surrounding concrete and the bricks of the Courtillières.

And in the image, also, of this so particular eco-system, welcoming a biodiversity fond of wetlands that represent the lands of Vertus. Where you can see wild rabbits, European hedgehogs, red foxes, and even parrots in their natural state.

A media challenge

According to an investigation dated April 14, 2021 published by the newspaper MEDIAPART, Grand Paris Aménagement would have called upon the communication agency PUBLICIS in order to avoid « a significant image risk ». This is a major issue for the public developer, owner of the land on which the gardens are located, and whose communication, until now based on the « eco » dimension of the future district, is undermined by the scheduled destruction of part of the Vertus gardens.

In addition to the retribution of a private group by an organization operating with public money, it is the strategic line adopted that is problematic. Focused on « key messages », it puts forward the harmfulness of the defenders of the Vertus, using ecology to harm the general interest. This general interest is that of an eco-neighbourhood open to all, making attractive a city with a precarious image. It is also a swimming pool that will benefit everyone, in a department where one child out of two does not know how to swim when he/she starts school.

The axis of defence of the development project is thus achieved by reversing the posture of defender of the common good: the resistors of the Vertus are described as « an agitating minority » going against the « positive character of the work for the city ». Behind this communication, the manoeuvre is a desire to discredit a more local approach to sharing in small private groups, which is to be contrasted with the sharing of common facilities.

An ideological difference is also a generational difference: the majority of gardeners are over 60 years old. Coming from a working-class background, they are more sensitive to a direct organized mutual aid, where each one exchanges his productions against those of the neighbour, or even gives them. Even as a visitor, it is not uncommon to be offered hospitality, leaving with products from the garden as a thank you.

The very model of occupation of the plots is done in a very communitarian way: if the price of the subscription to occupy one is quite affordable (starting at 32 euros per year for a surface of 150 m2), the gardener has the task and responsibility to maintain his plot well, under penalty of being pushed out by the association. However, to have the chance to have one's plot of land here is deserved, and sometimes one has to wait several years on the list.

The PUBLICIS file points the finger at this mode of operation, reproaching it for its excessively exclusionary nature. This criticism echoes another one, this time addressed to the public authorities by the opposite camp: that of exclusion through the wallet. Indeed, if the conditions of access to the aquatic centre are still unknown, other equivalent structures, installed in Seine-Saint-Denis, would already give an idea. In Aulnay-sous-Bois, a swimming pool built by Spie-Batignolles - like the one in Aubervilliers - and also having the Olympic Games 2024 label, charges 15 euros for access to the balneotherapy area, in addition to the price paid to access the pools (between 3.30 and 6.50 euros)A sum which would be more than consequent for a piece of equipment supposed to be accessible to all the inhabitants of the city, without restriction.

The last stand

On April 17, 2021, at the initiative of Save the Aubervilliers workers gardening lots collective, as well as several other organizations, a demonstration was organized to oppose the destruction of part of the plots. Along a march from the city hall - and from the Church of Notre-Dame-des-Vertus which faces it - about 1500 people showed their support for the cause.A march that ended on gardens, even to the detriment of the association’s opinion. Mainly composed of elderly people, supported by a prefectural decree that fell during the night and by the risks linked to the COVID, this one had informed the organizers of their will not to make the demonstrators come in the Vertus, despite their satisfaction to see such popular support to their cause.

A request however not heard. After some jostling, the plots were filled with people, while some gardeners preferred to stay outside, fearful of the consequences of the density of participants and the risks of police intervention.

A «last stand» for Gérard Muller, happy that the message was heard but somewhat annoyed by the turn of events. But also the first external signs of the fundamental rupture between two organizations claiming to defend the gardens: the Vertus workers gardening lots association and the Save the Aubervilliers working gardening lots collective. If the first one includes only the gardeners and aims to represent them, the second one, having for specific action the fight against the development project threatening a part of the gardens, has a much more political aim, in a global reflection on the place of nature in the Greater Paris. Although it counts only a few growers of the Vertus as members, it has gradually appropriated the fight, sometimes at the expense of the association’s opinion, as was the case during the demonstration of April 17.

And it is thus that for the external organizations participating in the march, such as Saccage 2024 and the National Movement of Fight for the Environment, it is of a more general fight of which it is questioning. That of the threat of the living by the works of the Greater Paris (the construction of the media village on the Georges-Valbon park in Dugny, the new road interchange at the boulevard Pleyel, etc.), and of which the destruction of the gardens is only one case among others.

If for Gérard Müller, «there is nothing worse than silence», the struggle is however in his opinion long lost, and the real fight consists mainly in organizing the aftermath: the displacement of fruit trees, access to water, the moving of the farmers to new plots. Far from the optimistic slogan of the demonstration: «Let’s save the Vertus workers gardening lots from Fort Aubervilliers». For the association, there will be no rescue.

click to view the complete set of images in the archive