Inside The Red Zone

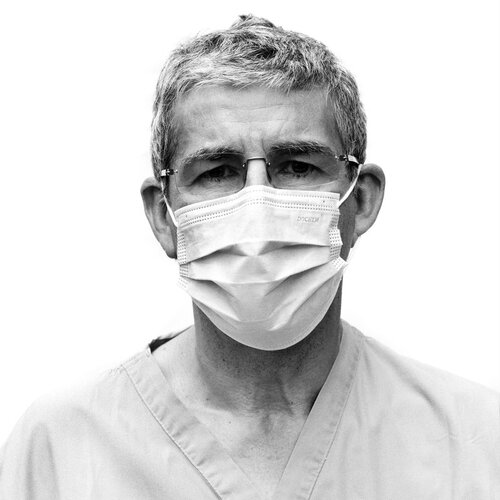

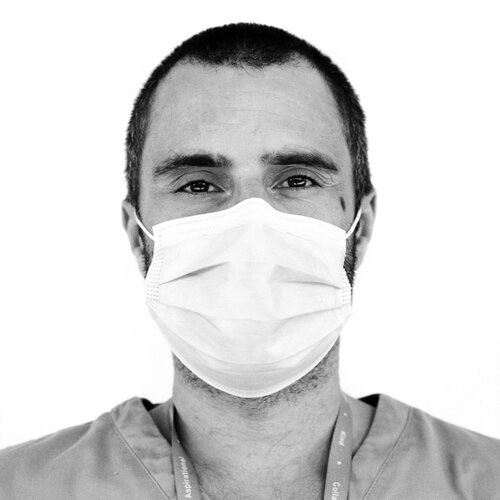

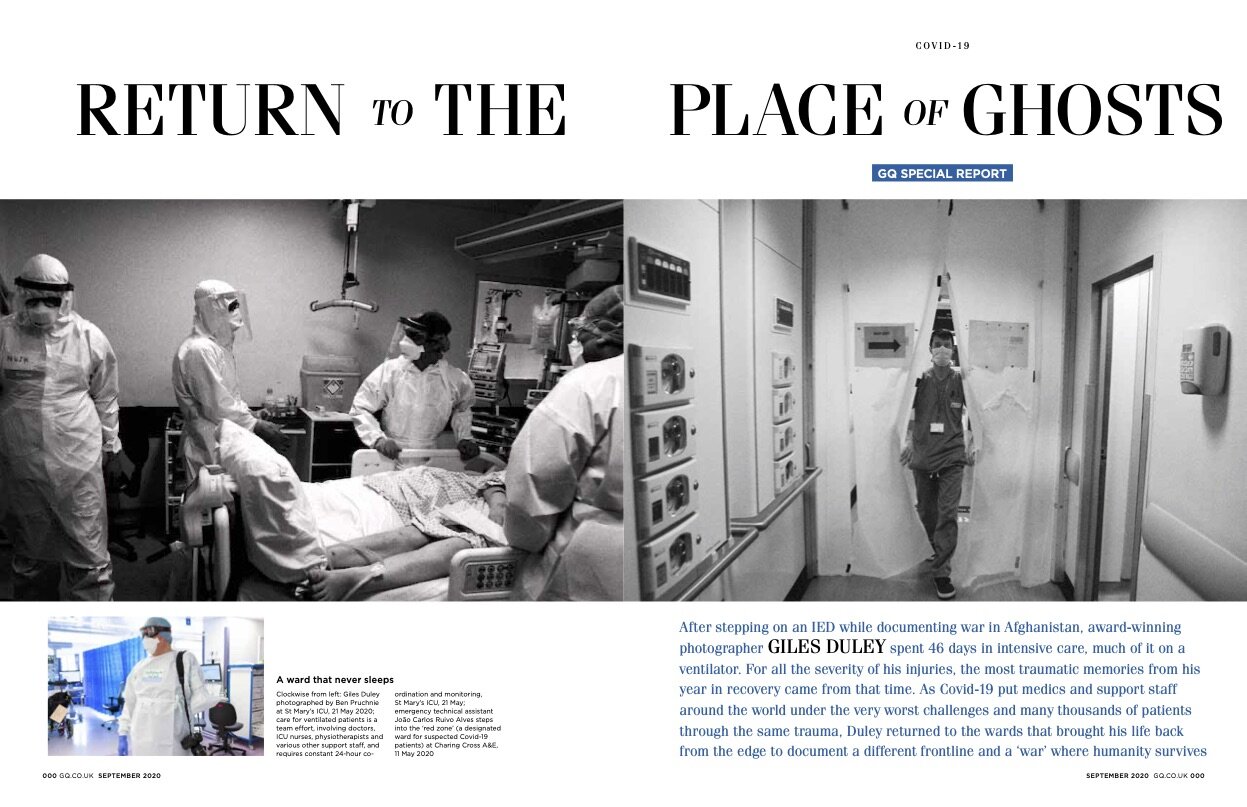

© Giles DuleyFor two weeks I’ve been documenting the response to Covid-19 by Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust in three hospitals; Charring Cross, St Mary’s and Hammersmith. From A&E to the laboratories, admin staff to ICU nurses, the first ward to be switched to a Covid-19 cohort and heart surgery; I’ve seen the complex, multi-discipline response to this crisis by the NHS. What has struck me most is the professionalism and calmness and most importantly the sense of being a team where every player is crucial. After one meeting a nurse pulled me aside and said’ “please make sure you document the work of the cleaners, they’ve been amazing”; after another a junior doctor asked me to make sure I focus on the nurses. Everybody is full of praise for their colleagues. Again and again I’m told “I only got through this because of the support of my team”

This project has particular meaning to me. Following an accident in 2011 I spent a year in hospital, much of that time in wards of the hospitals I’m now documenting. Some of the staff I’m now working with, were responsible for saving my life, indeed it was they who asked me to come and document the hospitals. It was the 46 days I spent in an Intensive Care Unit (ICU), much of that time on a ventilator, that left the most traumatic memories and returning to one not an easy decision. The nightmares from that time have never left me.

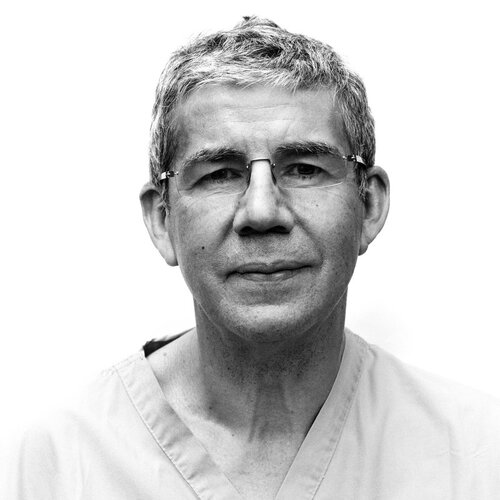

To enter an Intensive Care Unit at night is to enter a place of ghosts. It is a place between life and death, where patients’ lives are maintained by machines and drugs that take over many of the body’s functions. The doctors and nurses, like modern day alchemists, control the ventilators, drips, PICC lines, medications and monitors that sustain life. It’s a constant process that doesn’t stop, even through the night the patient’s bloods and vital signs are recorded, analysed and adjustments made. There is a constant whir of servos, bleeps and alarms; lights flash, monitors record the slightest change in vital signs. An ICU unit is like the set of some dystopian sci-fi film.

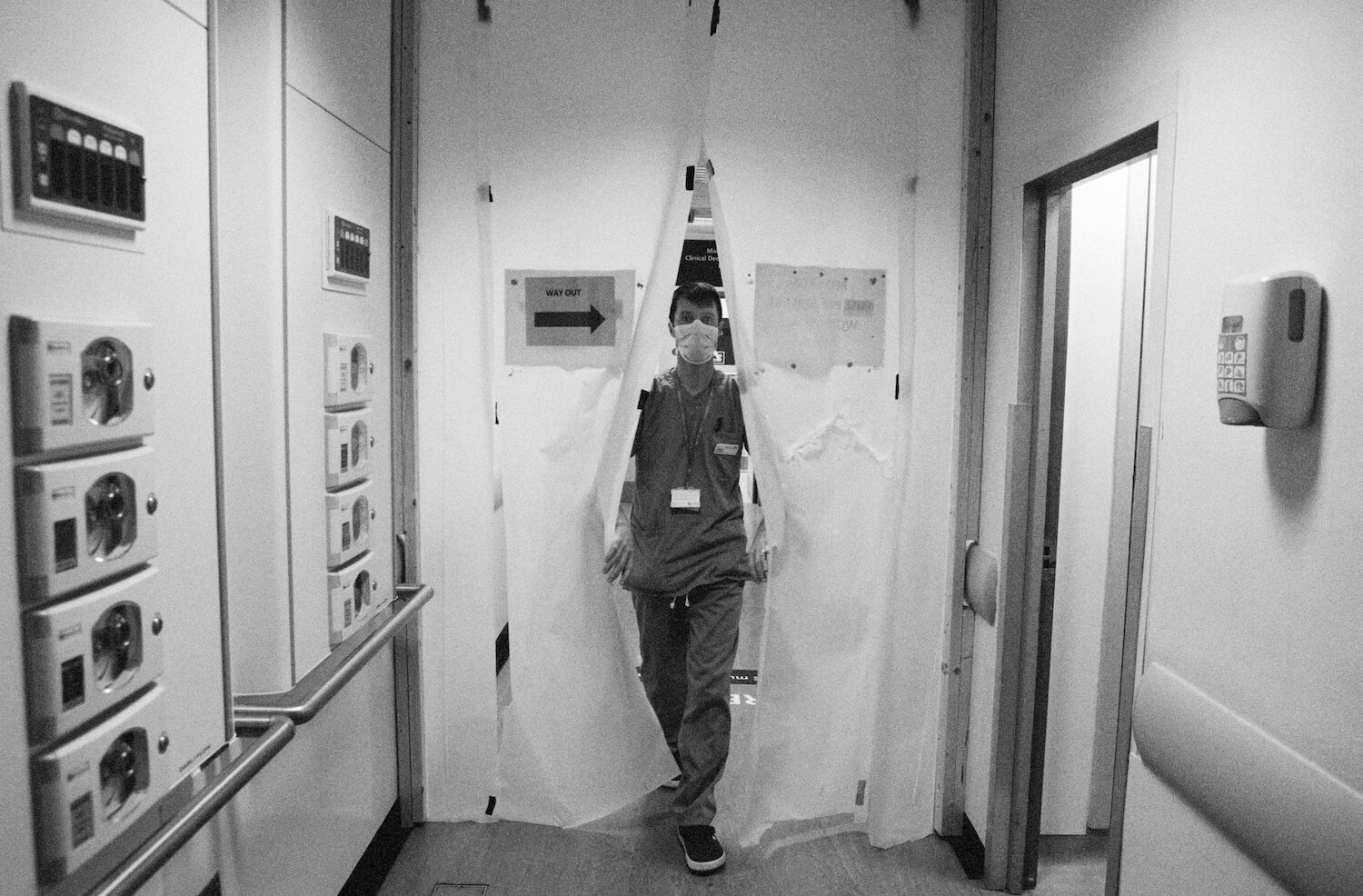

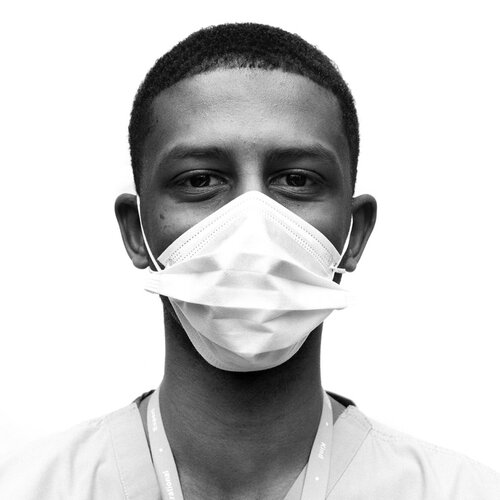

This work was hard enough before Covid-19 but now the task is a brutal physical battle for the ICU staff. Scrubs, gloves, apron, shoe covers, disposable apron, mask, visor, second gloves and then tape must all be donned before entering the unit. Its unbearably hot and hard to breathe through the mask, the simplest of tasks is exhausting. Like a grand prix driver the staff are pushed to the limits of endurance whilst having to stay alert as a moment of distraction could prove critical to a patient’s survival. As the PPE takes so long to remove its impossible to stop for a sip of water or to take a toilet break. The teams are working twelve hours shifts, often with only one break.

A Covid-19 Intensive Care Unit is brutal. The cold environment, the physical strains, the knowledge that half the patients won’t survive. Yet despite all this, what I find in these units is the greatest of humanity. The staff go about their work with professionalism and focus, they are the strongest of teams, all supporting each other and most movingly they treat their patients with such compassion and dignity. As the doctor’s do their rounds, even though most patients are in induced comas and those conscious are barely responsive; they take their time and talk to their patients, hold their hands, comfort and encourage. The nurses, despite being under so much pressure, do the same; always explaining what they are doing, looking into the eyes of their patients as the inject drugs through the PICC lines or take more bloods.

“Being here was a stark reminder of the fragility of life”

One patient has been taken off the ventilator and is slowly waking from his induced coma. Confused and disorientated by the drugs still in his body and unable to speak because of a tracheostomy, he taps on his phone. No personal items are allowed in ICU, the staff must leave their mobiles and even id cards outside, the one exception is each patient has their phone with them. As no family members are allowed to visit, this is their only connection to the outside world and their loved ones. He taps the phone again and a nurse picks it up. “You want to speak with your family?” she asks. His eyes widen in plea. She tries to unlock his phone, but is unable. The patient still too weak to do it himself. She places it back down beside him and squeezes his hand; “We’ll figure it out, I promise. Till then I’m here.” A doctor also by his bed leans over, “you are doing so well. I’m so proud of you.”

Politicians and media constantly use the analogy of this being a war and the medical teams being at our frontline. I have witnessed war and I can tell you that this is the opposite. War is devoid of humanity, its is inhumane and cold; what I see in these hospitals is all that is good in humanity. The medical teams, despite being under unimaginable stress go about their work with gentleness, compassion and kindness that witnessing has left me humbled.

And let’s be clear, this did get close to overwhelming the NHS. This virus is complex, aggressive and still not fully understood. And for the teams they are dealing with the realisation that what started as a sprint is turning into a marathon. The analogy most used when describing it to me is the AIDS epidemic; patients often present with confusing and unique symptoms. In the worst cases it seems to be the body’s own response to the virus that is proving fatal. The most serious cases are a puzzle that challenge the medical staff. I’ve documented frontline hospitals in warzones, Ebola outbreaks and worked with medical NGO’s in other humanitarian crisis and this virus is deeply worrying; this is not the flu. An uncontrolled second wave or a slight mutation is the virus could be catastrophic. As for the potential devastation it could cause in developing countries or packed refugee camps; its unimaginable.

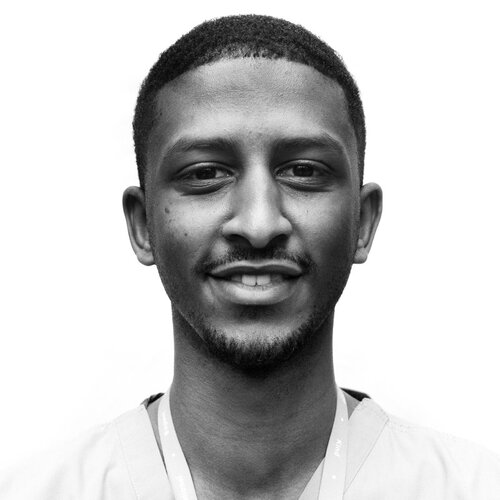

The majority of the staff don’t like the word heroes. It is of course used with best intentions but there is a danger we forget that the staff are human. Cleaners, porters, nurses, doctors, admin staff, lab technicians; they have all been put under incredible strain for the past months and many will need support in the months ahead. These also need us to do our part in making sure they are not again faced with the level of pressure reached at the peak.

So I will avoid calling them heroes, but as a witness to their work I will say they represent all that is good in humanity. They are the best of us, and as lockdown eases we should be proud of them and thankful to each one. They have put themselves on the line for us, and we should never forget that.

The feature was commissioned and published in the September issue of British GQ with the kind support of Imperial NHS and Pulitzer.

click to view the full set of portraits

click to view the full set of reportage images