Iraq: An Open Wound

© Giles Duley“Few stories have affected me as much as documenting injured civilians from Mosul. A trip in March 2017 that left bereft of hope, and questioning the validity of the work I do. For a month after returning, I didn’t feel like speaking to anyone, just hid from the world. When faced with such darkness and violence, what value can a photograph have? Does it become just voyeuristic to capture and share those moments? Against such horror a camera seems impotent, its use almost perverse.”

I believe photography comes with great responsibility, as soon as I lift my camera to record somebody’s story; I have to ask myself ‘why am I doing this?’ Especially when that work is documenting another’s suffering, nothing in photography goes more against human nature; the process of pointing your camera at somebody injured, afraid or in real peril. So why do it? Does it make a difference?

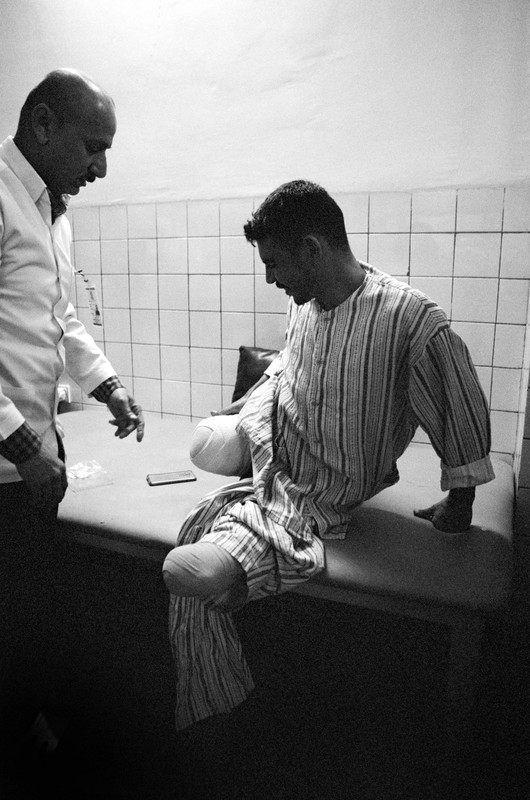

In March of 2017 I was based in a hospital run by EMERGENCY in Erbil. Everyday they were receiving dozens of badly injured civilians from the fighting for Mosul. After over a decade of photographing the effects of conflict, the scenes I witnessed there were amongst the worst I’d seen. Babies with amputated limbs, whole families lost, a young child paralysed by a sniper’s bullet. It was beyond words.

In the past I have referred to how I always try and find a positive in such situations, a moment of humour or to show the love between loved ones. But what I witnessed from Mosul left me beyond that, there are times you can find no such image. I think of Raghad, for four days I watch him silently sat by his son’s bed. He nods when I walk by, nothing more. Then one day he comes over and grabs my arm.

“It was not my fault,” he pleads through dead eyes, a hollowed expression I have rarely seen, “I did what I though I was right.”

He goes on to tell me his story. How his family sheltered beneath a table in their home as bombs landed around them. The house opposite was hit, then the house next door, at that moment his nerve gave and he’d told his family they must run. As they left the front door, a third bomb smashed into them. Firas’s wife, three daughters, two sons; all killed instantly. A son, Abdulah, left blind in one eye.

There is nothing one can say to such a story, you cannot say ‘things will get better’, for they never will. There is no hope or positive angle. This is the real face of war and its sinking, sucking horror.

I photograph his son against a white wall, a patch still on his eye. Skin pitted by shrapnel, his expression as hollow as his father’s.

I could only see the darkness and horror of what was happening. I was shooting angry, taking away my normal working practice of not showing the blood and gore. I wanted the world to see what was happening and to reel away as I had.

As the days passed, I knew this was wrong. It was not about me, it was about those I was photographing and to do their stories justice I had to work in a balanced way. I don’t like the phrase to give people voice, they have voices, my job is to make sure those voices are heard.

But still that question, why do it? What difference will a photograph make anyway? Only recently I’d heard my inspiration, the war photographer Don McCullin say there was no point in his years of work – because wars still go on. So if my photograph makes no difference, why point my camera at a child who’s just been injured? It’s an intrusive act and one that must have a purpose.

View fullsize

On the last day I’m there I am sat with Dawood Salim, a 12-year-old boy who had lost both of his legs and most of his right hand. For the past week I’ve been visiting him and his mother, he always smiles and jokes. For the first time, I feel ready to take his photograph.

I ask his mother, “do you mind if I photograph you son?”

She looks at me, with a defiant yet resigned stare, “When a child is injured like this, the whole world should see.”

Is that an answer to my doubts? Does that make it all ok? Of course not, but it reminds me of my simplest role, to act as a witness, to tell their story. What Dawood’s has said has not given me permission; it has challenged me to do what she has asked. There is no point in taking a photograph if I do not then do all I can to make sure the whole world sees it. That is where my duty lies.

click to view the complete set of images in the archive