Prismatic Realm

© David MaiselIn 2004 and 2005 I traveled to Iceland, inspired by a grainy B/W photograph I’d seen on the front page of the New York Times several years earlier of an immense canyon with a tiny speck of a Cessna airplane barely visible within it. The caption read “A small plane flying through the Dark Canyon, whose water flow will be all but stopped if Iceland dams the river to supply power for a smelter."

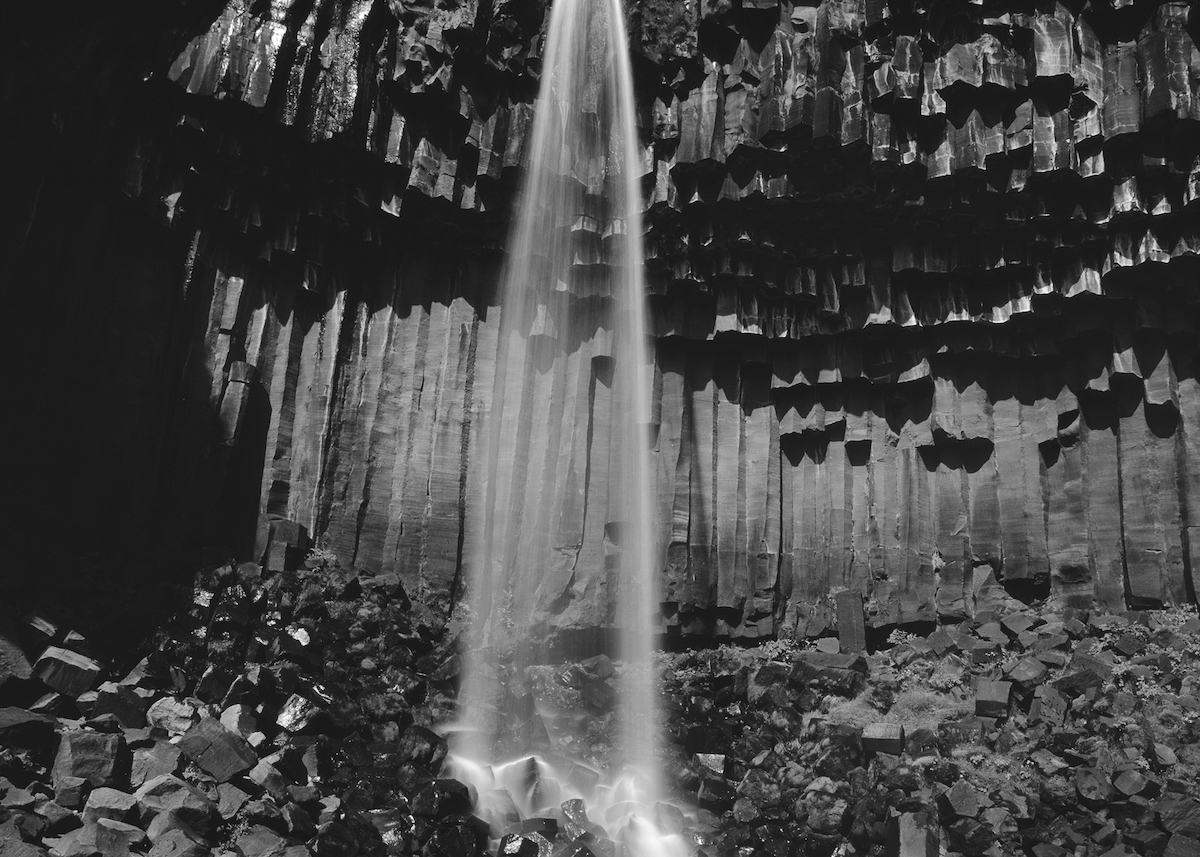

To experience the Icelandic terrain is to engage with the sublime. Water rushes over falls, it freezes, melts, and calves. Steam vents smolder, volcanoes erupt. Most travelers visit to feel compelled by the awe of nature; as they move through these spaces, they encounter a scale that is vast and magnificent. The lungs and heart expand to take it all in.

In the more remote regions of the island’s Highland interior, though, industry had begun to take the land apart, as forewarned in the New York Times article. In 2004, I was able to witness the initial phase of construction of the dams, reservoirs, and underground tunnels of the infamous Kárahnjúkar complex, built to power Alcoa’s aluminum smelting plants. To create the Kárahnjúkar hydropower plant, five dams were built across two glacial rivers, creating three reservoirs that flooded over 440,000 acres of pristine terrain — some 3% of Iceland’s land mass.

On my second visit a year later, we were denied access to the site. The creation of Kárahnjúkar – on the edge of the Vatnajökull National Park, in the largest high desert wilderness in Europe – became a pivotal moment in Iceland's growing backlash against environmental destruction. Protesters chained themselves to construction machinery and formed a human chain to block workers from the site. The conflict was due both to the scale of the project and because it was seen as part of an enormous investment in hydroelectricity for the benefit of aluminum multinationals such as Alcoa, no matter the cost to the environment. Despite local and international controversy, the project was completed, and Alcoa’s aluminum smelter was fully operational by 2008.

In this series of photographs, I formed a prismatic view of this island nation – the public spaces of idealized nature, where visitors have experiences of the transcendent – and the remote, inaccessible zones where industry dismantles the land and converts it to raw energy.

click to view the complete set of images in the archive