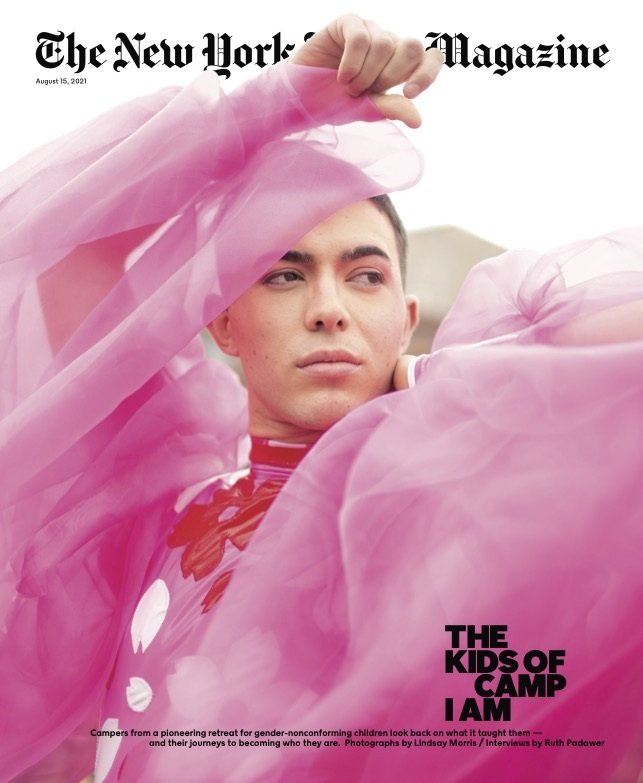

The Kids Of Camp I Am

© Lindsay MorrisThe Kids Of Camp I Am is the follow up from You Are You

Fourteen years ago, a Massachusetts mother of a gender-nonconforming son organized a tiny ‘‘summer camp’’ of sorts, where for several days her child and others like him could openly wear frilly pastel nightgowns and tend to their My Little Ponies. Three other families showed up that year. As the campers played together, their brothers and sisters discovered that they weren’t the only kids whose siblings wanted to be princesses — and their parents found support as they grappled with next steps. At the time, it was perhaps the only camp in the nation for kids who are now sometimes called ‘‘gender fluid’’ or ‘‘gender expansive,’’ children who, regardless of their gender identity, don’t want to be confined in their clothing and play by society’s prescribed boundaries.

More families — from Arizona, Illinois, Indiana, Maine, Mississippi, New York, South Carolina, Texas, Utah — started going to the camp, most of whom discovered it through a private listserv connected to one of the few programs at that time for gender-fluid youths, run out of Children’s National Medical Center in Washington. Almost all the campers were assigned male at birth. Some were OK with being boys, as long as they could do things that girls were allowed to do. Others knew, or would soon know, that they were girls.

Over the years, the various organizers, all volunteers, insisted on keeping the camp’s existence quiet: They avoided advertising, and each new family was vetted through an hour-long interview to make sure they weren’t anti-queer trolls. Most summers, camp was held at a Wisconsin retreat center offering four or five days of intense camaraderie that the children, parents and siblings shared with almost no one else. While the children ran around in shimmering mermaid tops, flouncy skirts and glittery pink barrettes, their parents gathered to share their hopes and challenges and get advice from experts. It was called Camp I Am.

Ryan in 2021

Ryan in 2011

Ryan in 2011

Danny in 2021

Danny in 2021

Hannah in 2020

Hannah in 2011

Hannah in 2011

Lindsay Morris, a professional photographer, was one of the parents who took her son there. She photographed the kids swimming in the lake, roasting marshmallows and getting ready for the camp’s fashion and talent shows — images she eventually turned into a book, ‘‘You Are You,’’ which was published in 2015. Some of those photographs also illustrated an article I wrote for this magazine in 2012 about parents’ responses to little boys who were deeply drawn to ‘‘girl’’ things.

Elias in 2021

Elias in 2011

Elias in 2011Now that many of the campers are adults, Lindsay was curious about how camp affected them and whether it helped them forge their identities. She reached out to some of the early Camp I Am families and asked the campers if they would be willing to be photographed again for The New York Times Magazine. Of the eight whose photos are in these pages, half are trans women, with a range of sexual orientations. The other half are cis men who are gay — ‘‘cis’’ meaning having the same gender identity they were assigned at birth. These eight campers are not representative of how gender-nonconforming children on the whole will identify as adults.

No reliable data exists on that question, but experts say that when provided a supportive environment, gender-nonconforming children will live in a way that suits them, and some will even end up as straight and cis. (Given the harassment that L.G.B.T.Q.+ people often face, we are using only the campers’ first names to preserve a measure of their privacy.)

These days, it’s much easier to find a summer camp that caters to L.G.B.T.Q.+ youths than it was when Camp I Am was founded. The camp ended in 2018, but its legacy lives on in the people who attended. Elias, one of the former campers I interviewed, summed up its impact, a conclusion the others echoed: ‘‘Camp gave me memories of expressing myself freely and what it felt like to accept myself. And years later, that helped me realize that the things we did at camp weren’t actually something we had to leave in our childhood.’’

click to view the complete set of images in the archive

Nicole in 2021

Nicole in 2013

Nicole in 2013

Tavish in 2020

Tavish in 2010

Tavish in 2010

Stefi in 2021

Stefi in 2012

Stefi in 2012

This was commissioned by The New York Times Magazine