The New Gypsies

© Iain MckellI remember coming back from abroad, switching on the TV and seeing images of double-decker buses barrelling down leafy country lanes loaded with Dickensian characters sporting battered top-hats and Victorian frock-coats. It was Summer Holiday meets Clockwork Orange. These were the New Age Travellers of the Peace Convoy and they fascinated me. A year later, in 1986, when the Summer Solstice came round again, Margaret Thatcher sent in the troops and they smashed up the travellers’ vehicles under the pretext they were damaging Stonehenge. In reality, she was trying to quash this anarchistic Punk Hippie counterculture from fomenting rebellion. She thought they’d all just leave, pack up and go back to their homes. But they didn’t have homes. That was when the liberal British national Sunday paper, The Observer, sent me to photograph their route towards Stonehenge. I leapt at the opportunity. I felt at last, something new and exciting was happening in Britain, a new youth protest movement.

I was immediately taken with this idea of punk in the landscape, and these larger-than-life characters, who seemed to hark back to the extremes of the Post-Industrial Revolution—a blot on the British landscape. It was Biblical, filmic, gangs of urban subcultures let loose in a rural setting. It put the fear of God into the likes of Thatcher and the establishment. She thought she had smashed the opposition, the miners and the unions, but new opponents were taking their place—road protesters, rioters, gypsies, outlaws, subversives. Thatcher was determined to break up the working class hotbed of communism she feared so much from her upbringing as a grocer’ daughter in Grantham. She saw miners, unions, anarchists and youth subcultures as an enemy to economic progress. She broke up all the manufacturing industry in this country—car workers, shipbuilders, printers even—she closed it all down. She doubled the wages of the police and squashed any group that stood in her way. It caused a lot of upset with many—there were riots in the inner cities—Toxteth, Brixton, Handsworth, Moss Side. She was turning the UK into a brutal, Fascist police state. Singer-songwriter Billy Bragg emerged as a spokesman for the Left—a British Woody Guthrie. He drew connections in his lyrics between the miners and shipbuilders and the New Age Travellers and the Glastonbury music festival—it was the soundtrack of the era.

The second time I met them was fifteen years later, in 2001, once more at the Summer Solstice by Stonehenge. I returned there to see where the culture was now, and with the intention of taking some more portraits of people in their rigs (a Hippie bus). I had been told that at Stonehenge I would find 300 or 400 New Age Traveller buses in amongst other vehicles. It was clearly still a strong subculture movement but, within that ragtag jumble of travellers, I found a small tribe, a newly formed hybrid that had evolved from the bus to the horse and wagon. After the motorised vehicles left, I had an instinctive urge to ask the Horsedrawn when they would be leaving but realised they weren’t leaving because they were already there. They had nowhere to go. No work, no parties to dash off to. They were living there and getting on with it quite well. It felt so surreal, how suddenly the pace of life slowed down. I had stumbled upon the realisation of a completely different mindset. I found that really inspiring. I realised immediately that was the project I wanted to work on but had no idea I was going to spend the next ten years of my life working on it. I had again found something new that had evolved over the years from 1986 to 2001. Once again, there was a new way emerging, a pure way. Back then, I had heard of global warming, climate change, the depletion of the ozone layer—climate was becoming an increasingly important issue and here was a small group of various families, who for fifteen years were plodding away greener than any other element in society.

Ironically for me, I grew up with Stanley Kubrick’s science-fiction film 2001: A Space Odyssey, set in the near future when mankind would find its destiny in the stars. In reality, for me, 2001 was when I found the future. My destiny lay not in a state-of-the-art spaceship hovering over Stonehenge, but in a train of rustic gypsy wagons. It was also the summer before 9/11—Pete, one of the Horsedrawn, said, ‘It’s Vietnam all over again.’ Fashion reflects culture and the following seasons’ catwalk collections were all hippie and gypsy influenced. As the Western world went into a time of reflection with war looming on the horizon, popular culture looked to the open road.

The New Gypsies are not completely isolated from the twenty-first century. In fact, they embrace technology. Without mobile phones, for example, there wouldn’t be a community, because they wouldn’t know where they were. If someone finds a really good park-up down the A3, near Surbiton, for example, word spreads quickly. There is a grapevine and it is watered by the latest gadgets. Solar power too is incredibly useful—it’s free after all. That’s why I see the New Gypsies lifestyle more as science fiction than history, because it’s applying

new technology that leaves no carbon footprint, solar power, wind generators, the horse and the wagons combined. By the same token, many of the New Gypsies are craftspeople—carpenters or blacksmiths. It’s the eighteenth meets the twenty-first century and it could point a way forward to a planet in trouble. When cities and technology are wiped out, the Horsedrawn will be the survivors. I know where I’m going if it happens. The Horsedrawn are a mirror, which reflects our culture; their way of thinking being the opposite of ours. For example, when the wagon’s going down the road and there’s a traffic jam, cars trailing back there in the lane, Pete will point out: ‘It’s not the wagons that cause the traffic jam, it’s the cars.’

I was struck by their lateral thinking. It was so logical. Of course, without the cars, there would be no jam. It was this way of thinking, which inspired me to hold up my camera as the mirror to the mirror, the analogy of the analogy, photographic verisimilitude; to convey the idea that people can look in to this world and think, how very romantic, they don’t share the same creature comforts or they don’t look at life the way we do, but there is still something seductive about the image. We are happy to ignore what we’re really doing to ourselves and to our environment and what we’re leaving behind for our children. We seem quite comfortable in our way of thinking but psychologically, deep down inside somewhere, perhaps we’ve become aware that it is fashionable to be aware. We might still regard these people as the Untouchables like in the Hindu caste system—the unwashed unclean hippie gypsies, the lowest of the low. I’ve been very aware of those common perceptions when photographing my friends in the Horsedrawn, but at the same time, I notice that, in equal part to the social resentment, there is a deep-seated attraction to these people and their alternative lifestyle.

Obviously, the gypsy life has romantic connotations and that is heightened by the Horsedrawn tribe’s renunciation of engines. Maybe it is romantic in the summer when you’re playing around with the horses in the fields, tiptoeing through the lovely long grass and going to sleep under the stars bathed in the warmth of a beautiful summer’s evening, it resembles the virgin’s dream of running away with the gypsies. But then, when it starts to get chilly, cold, rainy and your friend Martin is found blue in his wagon, dead of pneumonia, then it’s hard and not so romantic anymore. You can be nice and warm in those wagons; warm as toast with the burners on, but it is a hard life right enough and several of the tribe talk about that, how the winter months are long and hard. I asked Pete why he lives that way and he simply replied: ‘Iain, I couldn’t live any other way. I can’t operate in the city. I just can’t function in society as we know it. This is the life for me. Hard or romantic or just the way it is, it suits me.’

They are keeping alive a valuable tradition and an alternative way of life. The New Gypsies make their own wagons and they are beautiful. They’re not off-the-shelf. It’s not like buying a bus or a caravan. You might know a little bit about getting an engine going but converting to horse-power was a conscious decision to eschew all of that. At the Big Green Gathering Festival, Pete runs a horsemanship and wagon class to anyone interested in the lost craft. There’s a lot to it, from harnessing a horse to riding a flat cart through a field, to feeding and maintenance, how to paint a wagon with the skill of a talented artist, designing and painting the ornate detail. There are also great musicians within the community. Both Pete and Dave have bands that play at festivals and music is the centrepiece to the evenings around the campfire.

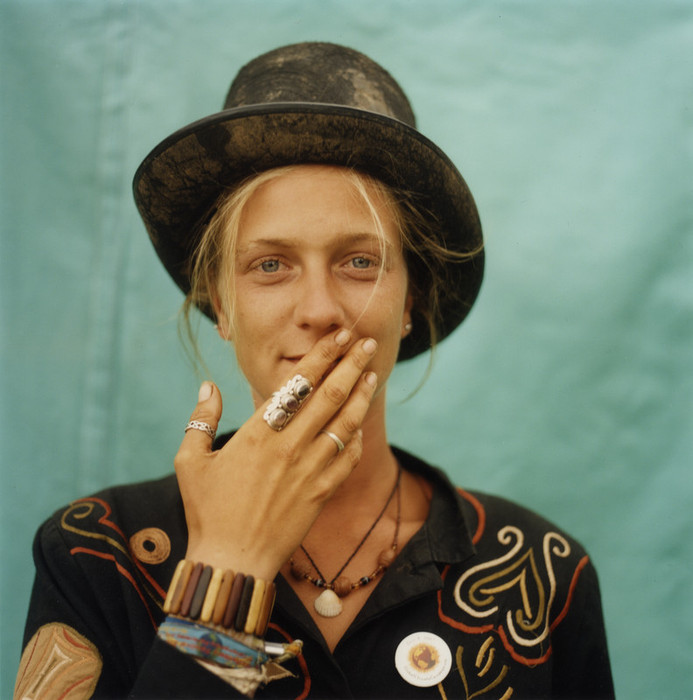

With this work I never set out literally just to photograph Horsedrawn people. Although my journey was with the Horsedrawn and they are the people that I spent my time with, it was through that journey with the Horsedrawn that I was introduced to a larger community of diverse characters. In fact, it has been ten years that I have been visiting this small group of around twenty people that I had formed strong relationships with. The girl Hazel, on the cover of this book, is one of them and now in her early twenties. She was 12 when I first photographed her with her parents Pete and Rachel along with her siblings Jordan, Bryony and Judah sitting up front of their wagon one Sunday morning. There were characters from different backgrounds who nevertheless shared an ideology and outlook on life. Whether it is a girl in green on a white horse; or one of the older characters like Sir John—a professional model-maker; or Holly, a local girl from a nearby village with her own horse, who likes to camp out with Hazel; or Drew, who lives in a horsebox (I couldn’t believe it at first, he had adapted it into a comfortable home, which, to the average passer-by, looks like an ordinary horsebox, a natural asset of the gypsy culture); or even Kate Moss. I found the broader concept of gypsies, their lifestyle and what they represent, could be pushed further than in pure documentary photography.

Kate Moss’ connection with the travellers is already there in one’s consciousness. The idea was underpinned by the link between the iconic Glastonbury festival, to which the Horsedrawn can be traced, and to the free festivals of the early 1970s. Kate Moss is a firm presence at that festival and has been going there for years. This is the environment where worlds cross. Global gypsy Kate Moss and the other extreme of a nomadic island tribe, the New Gypsies, come together through music and lifestyle. In these photographs, one may understand more about Kate Moss but, ultimately, more about the New Gypsies, when one realises that friendship transcends our perceptions of both traveller and supermodel.

There’s a lot of negative propaganda about gypsies—the stereotypes, the fear. They are perceived to be cunning and perhaps they are, but it’s a cunning borne out of necessity from vehicle travellers, the bad press and the police. They have trouble with the police, trouble with people generally. But the horse and wagon remains a romantic image. It is a great façade to delude, to romanticise themselves, which means they can be perceived in a different way. Essentially they’re travellers but, by having the horse and wagon, they’re received in a different way from motorised traveller

It’s ironic that I see the way of life of the New Gypsies as the future not the past. These are modern, predominantly city people who have moved out of largely working class urban communities, out of poor accommodation, escaped the shit being dumped on them. The greatest irony is that, they took Norman Tebbitt’s advice, got on their bikes (or wagons in this case), on the road and found freedom. Their freedom is not in this country but in their heads, where freedom is in the journey.

click to view all the images in the set

The Monograph

Publisher: Prestel

Paperback, with flaps

128 pages, 22.0 x 27.0 cm, 8.7 x 10.6 Inches

80 colour illustrations

ISBN: 978-3-7913-4996-1

click to buy the book