Tiaras, Tuxes and Reparations

Photos © Lindsay MorrisWords © Judy D’Mello

Given that it's prom season, I hope you will consider the following article about a recent prom party held for 65-year-olds

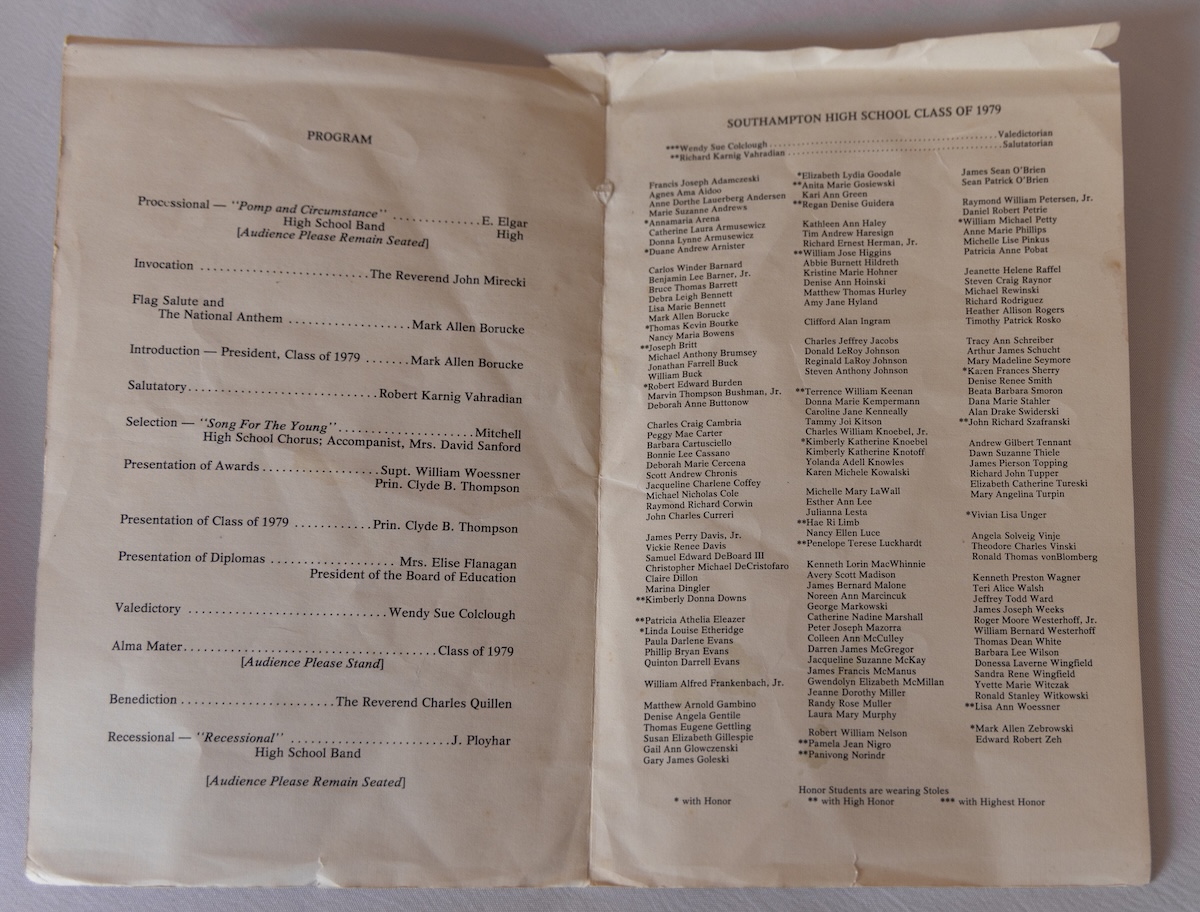

To be clear, this was not a reunion. It was a register of genuine progress 47 years in the making. As high school seniors in 1978, in Southampton, N.Y., Black and Shinnecock Indian students were told that they would not be allowed to attend prom alongside their white classmates at an event space in the Hamptons. Rules were rules and only whites were allowed to enter the first floor dance hall.

Almost five decades later, now senior citizens, the Southampton High School class of ’78 graduates, traveled from across the country to finally celebrate, as a unified group, this American rite of passage in the original space, thanks to the efforts of Hamptons Community Outreach, a nonprofit that works with the Shinnecock tribe.

--

Like crocuses pushing up through the soil, like a first glimpse of daffodil in spring, Rev. Tisha Dixon-Williams’s words on the evening of April 19, offered a flicker of hope in Southampton, N.Y.

“Tonight, you are not guests at this table — you are the reason for it. So I want to pause and thank you. For your patience. For your perseverance. For showing up tonight not out of nostalgia, but from a place of great strength,” said the senior pastor of the First Baptist Church of Bridgehampton in the Hamptons.

She was addressing the 60-plus people who had traveled from all corners of the country to attend an event that elicited more than a few double-takes — a prom party for 65-year-olds. Make no mistake, this was not a reunion. This was a group of white, Black and Shinnecock Indian seniors — as in senior citizens — who had shimmied themselves into bejeweled gowns and tuxedos, pinned on boutonnieres, slipped corsages on wrists, painted their nails and donned their finest wampum.

So, that quintessential American rite of passage, except for the elderly? No, this was a register of genuine progress 47 years in the making.

In 1978, as Southampton High School seniors, local Black and Shinnecock Indian students came face-to-face with the segregated realities of this town in Eastern Long Island when their prom became a flashpoint of institutional exclusion.

“A venue on Elm Street in Southampton had seemed like a good social space to have our prom,” recalled Denise “Weetahmoe” Silva-Dennis, a Shinnecock Nation tribal member who graduated from the school in 1978. “But the catch was any Black or Shinnecock kids who wanted to attend would have to stay in the downstairs area and not be allowed to go upstairs.” Only the white kids, she was told, were allowed on the first-floor space, separating children who had been educated together since kindergarten on racial grounds, according to the rules of the Polish Hall, an event space that’s now called 230 Elm Street. The class did have their prom in 1978, under a tent in a field, on a rainy, windy evening. “My hair got all messed up,” Ms. Silva-Dennis said, with a smile.

Fast forward to the recent mid-April evening, when winter melted deliciously into spring. Outside 230 Elm Street, Ms. Silva-Dennis stepped out of a limo, her hair curled and set, her beaded blue gown matching not only the cloudless sky, but the bowtie worn by her husband, Avery Dennis Jr., a 1972 graduate of the school and the son of Chief Eagle Eye, a Shinnecock tribal politician and activist. Only one thing shone more brilliantly than Ms. Silva-Dennis’s dress: her smile, confirmation that she was basking in the moment, bestriding the enormity of the occasion. She was, after all, the catalyst for the class of ’78 prom party redo.

It happened during a fundraising event in February at 230 Elm Street, hosted by Hamptons Community Outreach, a nonprofit that works closely with the Shinnecock Nation and where Ms. Silva-Dennis serves on the board. The organization’s annual Valentine’s event took place on the first floor, the very spot from where several of the tribeswomen had once been barred. That day, rather ironically, the same women were being honored for their contributions.

“Somewhere, whoever made those decisions back when it was called the Polish Hall, must be rolling in their graves,” Ms. Silva-Dennis remembered thinking before she told Marit Molin, the founder of Hamptons Community Outreach, about the historical events that took place 47 years ago. Ms. Molin was shocked and immediately knew that reparations were in order. She ran the idea to “right a wrong” by her board.

“We can’t change what happened in 1978,” she said, “but we can celebrate these remarkable people now and celebrate them in a space where they always belonged.” Hands flew up in support of a prom party do-over and the organization began fundraising and calling on favors to cover the event’s costs. Ms. Molin wanted to spare none of the requisite prom regalia — limos to shuttle some of the partygoers from the Shinnecock reservation to the hall; decorations in maroon and white, the school’s colors; a vast buffet of locally-prepared food; an open bar; boutonnieres and corsages; a deejay, photographer and party favors. She also offered to cover tuxedo and dress rentals, as well as travel costs for those coming from afar. It was undoubtedly a show of human will in the path of history and Ms. Molin hopes the event will inspire other communities around the country to do the same.

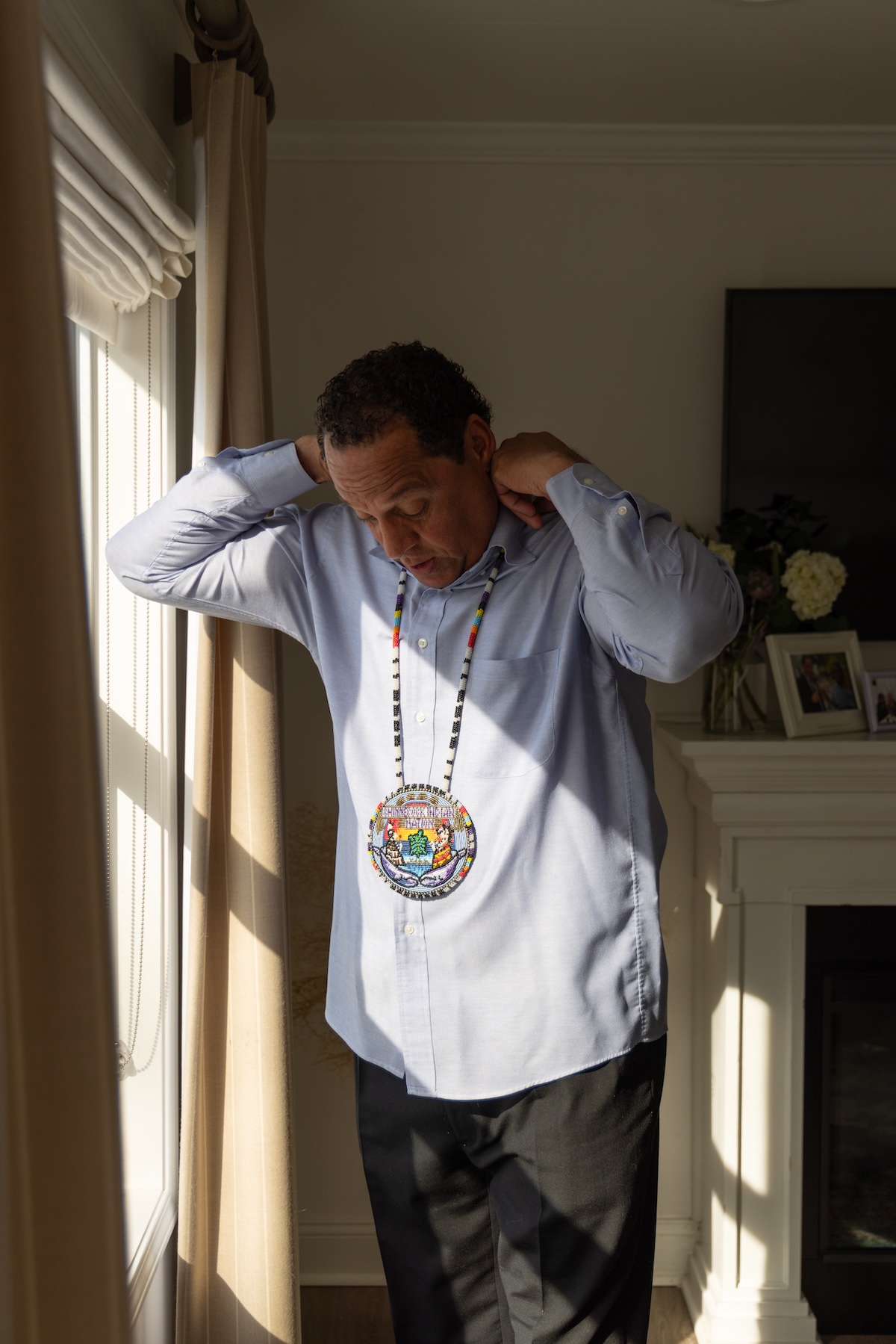

There was significance in watching Ferdinand (Ty) Lee, III, and his wife, Gloria Lee, who live on the Southampton reservation, climb the steps and enter a place where they were once unwelcome. Mr. Lee, a high school student athlete who went on to work for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, wore a hand-beaded Native American medallion around his neck, that depicted his tribe as whalers and people of the shore.

Valorie Hunter, a Black graduate, squealed with excitement at seeing her white classmate Mark Antiley, who was the class president in 1978, when the pair got the best dressed couple vote.

“Isn’t he handsome?” she cried, beaming at the rakishly still-good-looking Mr. Antiley, who is on the board of 230 Elm Street. Ms. Hunter, a nurse, made the trip from North Carolina especially for the event. As the pair hugged joyfully, another classmate walked by, waved her hand and said, “They’ve been crushing on each other since high school.”

Equally, it was sobering to hear Jennifer Cuffee-Wilson, an elder of the Shinnecock Nation who graduated in 1977 say, “Nothing racist in this town surprises me because it’s been the same since 1640.”

Ms. Cuffee-Wilson, a tall, stately figure dressed in deep, wampum purple to match her jewelry made of silver and the inner layer of quahog shells, from which the color is derived, held a walking stick carved by her nephew on the reservation. The year she referred to was whe Europeans settlers arrived in what’s now called Southampton, where her ancestors, th Shinnecock American Indians, had lived for centuries. Since 1640, the indigenous people hav endured land grabs, population loss, poverty, marginalization and other threats to their existence, including a lack of employment opportunities.

Holly Haile-Thompson, who traveled to the party from Mohawk Country in Canada, had skippe a year and graduated in 1977. She said she experienced racism first hand. “Graduating early was the greatest motivation to get away from the terrible treatment that Southampton displayed against Shinnecock people,” she said. Today, an ordained minister in the Presbyterian Church, she remembers being told by the school that she would not be allowed to take New York State Regents exams because she was from the reservation. One particular guidance counselor, she said, told Shinnecock students that they were not college material, that they would only ever be domestics.

Against this backdrop, came more from the Rev. Dixon-Williams. “This isn’t just a dance. It’s a moment of divine restoration. This isn’t just a prom. It’s a promise fulfilled. This isn’t just an event. It’s an exhale generations in the making.”

Yet, zoom out a bit and it became a story about human variables. Next to the bar, stood a group of white men, laughing, joking, slapping each other’s well-padded shoulders while the reverend delivered her profound and hopeful speech. Someone had to actually go over and shush them. There was also a man who said he was there simply to reconnect with old friends. And a woman of Polish decent, who, having spent her childhood going to the venue, shrugged off the 1978 events because it was, “a different time back then.”

“But, she showed up!” insisted her classmate Denise Smith-Meacham, a Black and Shinnecock grandmother who lives in Southampton Village, and who was nominated in 2022 for Suffolk County’s Woman of Distinction Award. “Many of our classmates didn’t know about what happened in 1978. But when I went on Facebook to let people know why this prom party was happening, they showed up. They showed up in support and that made me feel good.”

Ms. Smith-Meacham, wearing an iridescent, body-hugging gown, silver shoes, black opera gloves and a Venetian carnival-style mask, was the evening’s unofficial spirit animal, hijacking the mic from the deejay at one point to insist her classmates hit the dance floor. “I was there to have fun no matter what,” she said.

A single event doesn’t re-straighten the ship. For Gretchen Thies, who drove in from upstate New York, showing up out of respect was one small step of the many it will take going forward. “Our classmates are here because they also wanted to show respect for the native culture…and we can all now carry this forward by educating our children that everyone is important. This class of ’78 has really facilitated that.”

The evening ended with a prom queen crowned (Ms. Silva-Dennis) and the happy guests meandering out clutching goody bags and flowering plants. The venue was finally empty, except for the Rev. Dixon-Williams’s words that everyone hopes, will reverberate forever.

“You see, there are moments in history where joy was stolen in silence. Where celebration was denied without explanation. Where young people—like you once were—were told without words that they didn’t belong. Where institutions, systems, and people decided that your presence wasn’t welcome in the room. And yet, here you are. Not just in the room. But owning it.”

This story is available to license