Truth In Fire

© Tim GeorgesonThe catastrophic 2020 Australian fire season was not just noteworthy for the unprecedented scale of the fires but for the way wet rainforest regions that had never seen fire burnt with the same ferocity as dry eucalyptus forests. In the following year in the high alpine regions of the American Rockies, forests thought to be beyond the reach of fire were also burning for the first time in recorded history while unprecedented heatwaves in the Canadian arctic and the Siberian Taiga led to fires in places which, until now, no one had ever imagined would burn.

The spread of these catastrophic fire seasons to regions that were once thought to lie beyond the reach of fire is evidence of how Global warming is reshaping the world. In the midst of this unfolding climate emergency, extensive, out of control fire has become a terrifying warning of what the future might hold.

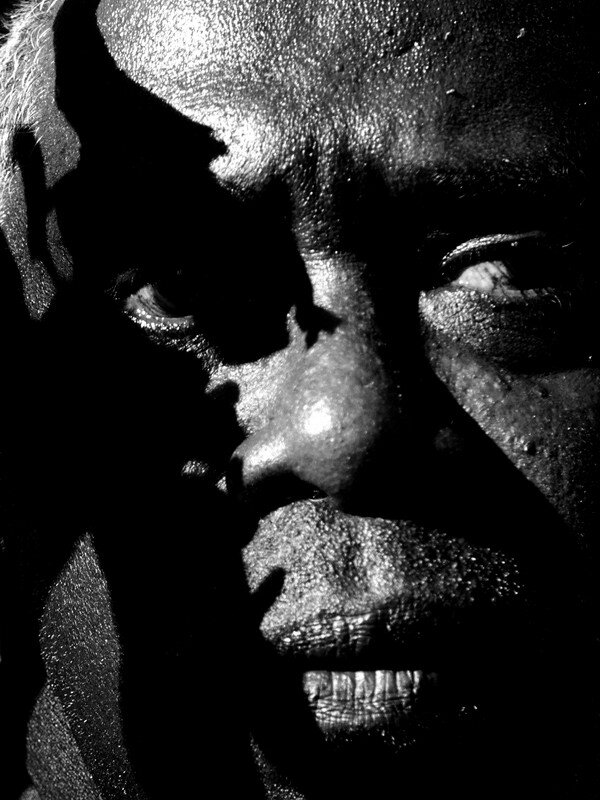

For Tim Georgeson, the decision to bear witness to this climate emergency began in the southern summer of 2020, during the Black Summer fires when he first saw his Australian homeland ablaze. The devastation of his nation became a call to arms that led him on his own journey of discovery. It’s a journey that began in despair, but which ended with hope as he connected with indigenous communities whose knowledge of cultural “cool burns” opened his eyes to a new way of living that could radically change our approach to fire management and global warming.

This collection of photographs map that journey. It begins in 2020 with Tim travelling to the New South Wales south coast to photograph the aftermath of Australia’s worst recorded fire season in a series of images that explore the utter devastation wreaked on the landscape. It was here that he made a connection with the Yuin community who would show him another way of approaching land management.

“These fire practices have been used by Australian First Nations people for thousands of years”

The indigenous Yuin people of the Shoalhaven were one of the worst affected communities. They had been warning of the impending fire crisis for a number of years. They could see that the country was “sick” as a result of the poor land management by National Parks and Government authorities. Too much understorey from poorly implemented backburning had led to tinderbox conditions. Yet their complaints had been ignored. Now, in the wake of these fires, the case for greater indigenous involvement in land management was made clear. Their understanding of the land comes from tens of thousands of years of “living in the country”. They not only knew when the country was sick, they knew how to heal it. And the answer was a fire. Not the terrifying hot fires of summer. But the “cold fire” of cultural burns.

The Yuin community embraced Tim and his interest in their knowledge of land management as a chance to inform the wider community of their mission. They invited him to document community leaders, such as Noel Webster, Vivianne Mason and her Granddaughter Ashweeni in their use of fire knowledge to heal “sick country”. It was here that Tim discovered an antidote for the despair he felt in the aftermath of 2020’s devastation.

His involvement with this community and their technique of cultural burning led him to meet Oliver Costello and the Firesticks Alliance, a national organisation devoted to teaching and promoting the use of traditional burning techniques for land management.

Tim began documenting the work of this organisation in the hope of capturing their central mission, to preserve the connection of culture with the land. For these indigenous communities, knowledge is country. They are one. In the driest continent on earth, fire management was a critical tool for keeping communities safe, but also for the way it “shaped” the landscape.

It was the Firesticks Indigenous Fire Knowledge Alliance that introduced Tim to the fundamentals of this knowledge. The need to understand how each region has its own kinds of seasons. Then understanding how to read the land and know what season was right for what kind of fire. Correctly timed and applied, cold weather, “cool burns” reduced fuel loads, at the same time as they encouraged propagation, increased soil fertility and selected the right kinds of plants to grow. These burns were low intensity and slow, so the fauna was able to avoid the fire.

But these techniques were being used on land which had been mismanaged for centuries. Tim wanted to connect with indigenous communities who were using these techniques on indigenous land.

In the summer of 2021 he travelled to the Kakadu region of Australia's far north to work with Minitja man and one of the traditional owners of Kakadu, Victor Cooper. Victor was renowned as a community leader with a deep understanding of Cultural Burning. Unlike other parts of the country where culture and intergenerational handing of knowledge has been broken down by colonialism, Victor’s knowledge has been passed down to him in an unbroken chain of stewardship that stretches back tens of thousands of years. And that knowledge had never been so important.

The Kakadu region is a vast and complex ecosystem that includes tropical savanna and freshwater wetlands. It had been under the management of its indigenous owners for tens of thousands of years until the arrival of the Ranger Uranium Mine and the National Parks Trust who began a system of severe back burning during the extremes of Australia’s decade long “Millennium Drought”. Victor had lived with the effects of this backburning, witnessing how it was reshaping the land of his ancestors. Which was why he and fierce eco-warrior Mandy Muir had led a campaign to reinstate traditional land management techniques in the Kakadu region.

Tim arrives in the prelude to the “hand back” when the indigenous owners would once more be allowed to care for their land using their knowledge. Victor invites Tim to “walk the country” with him as he shows him how much of the land has been damaged. But then he introduces him to the beauty of the untouched Kakadu wetlands, where the cool burning technique is used to manage the environment. Here he is witness to the incredible complexity and richness of an ecosystem which “works” with its indigenous owners. Cool burns were used during wet seasons to manage growth and keep the understorey clear. They were also a central part of the propagation of plants that were beneficial to the fauna that Victor and his community hunted.

It is here that Tim begins to understand the true wisdom of indigenous land management. That the connection between land, knowledge and culture is continuous. This is why he hopes that the work he collected in this journey will inspire new cross-cultural understandings that support international climate movements, as well as initiatives for new legislation at the state and federal levels which will allow First Nations people to participate in the ecological decision-making around crucial ecological survival issues. He has seen first-hand how deep and extensive the traditional knowledge of the land is and how important that knowledge is to shape our response to this climate emergency.

click to view the complete set of images in the archive