The Tennant Creek Brio

© Jesse MarlowThis is a wonderful story about a group of men struggling with alcohol brought together by an ex AFL player Rupert Betheras who was initially employed by Anyinginy Health to deliver an art program through group therapy, focusing on social and emotional wellbeing.

The Making of the Tennant Creek Brio by Anna Krien

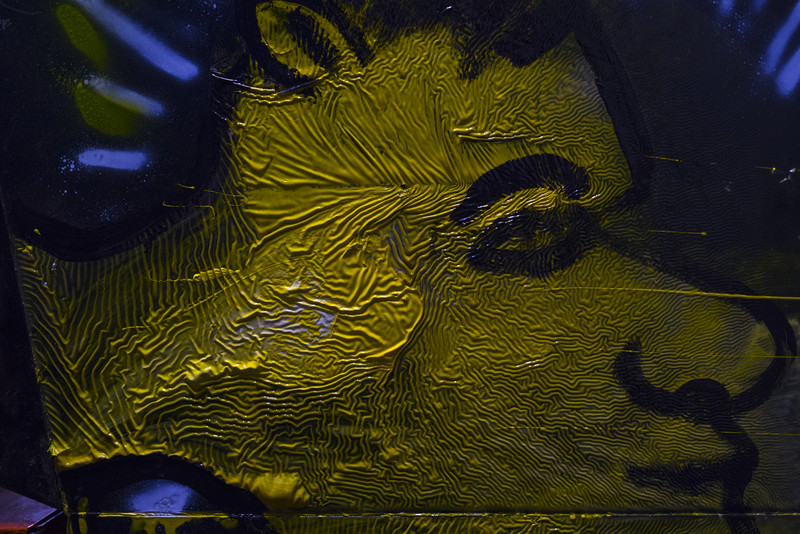

Paintings of dust storms on shattered television screens, gambling machines covered in traditional artwork and speared, unfurling tentacles of enamel paint and enormous mystical creatures in bold brush strokes – this is the work of the Tennant Creek Brio – a group of men who began painting in an art therapy program four years ago in an Australian desert town largely known for its shocking headlines of violence, alcohol abuse and poverty.

Set on the highway, a silver bitumen zip up the centre of Australia, Tennant Creek is slam-bang in the middle of the renowned Western Desert Art movement – and yet few have held out any hope of this particular town making a mark on the scene. Tennant Creek is an outsider town, existing on the fringes of both white and indigenous worlds, and it is fair to say, no one expected a single bloom between them.

Enter Rupert Betheras, an artist and ex-Aussie Rules footballer, who led the art therapy group with absolutely no therapy and pure dedication to the medium. Under his tireless direction, the indigenous men began to paint extraordinary works on Masonite boards scavenged from trucking yards and on the dead screens of televisions. Setting up at a former workers’ depot, the tin sheds were turned into studios and the indigenous artists drift in at night when the temperature finally dips below the forties. Every night Betheras is there, already painting and waiting for them.

Today the collective calls themselves the Tennant Creek Brio and there is a buzz about their bravado. Currently on show across all three venues of the 2020 Sydney Biennale; people are flocking to see the extraordinary towering works on Masonite boards, painted televisions hanging from meat hooks and one-armed bandits (Aussie slang for gambling machines) painted, speared and left to bleed out on the concrete floor.

The Brio is a loose nine, and among them is Fabian Brown. Wiry and charming, the 51-year-old paints ogres, mystical animals, mermaids and bulky policemen, curiously unique and instantly recognizable forms; his unusual vision is like a haunting collage of radio and TV fragments, a stapled together way of seeing the world. Often, Brown paints on top of Betheras’ paintings – thrilling vivid abstracts - and their work creates a wondrous and compelling dialogue between two artists; a Western desert man and a European man.

Their series of towering Ancestor Boards -Life Cycle, Warrior, Horus, The King, Bluebird, Werewolf, and She-Wolf, have been purchased by an anonymous collector and yet, in the tin shed, none of this matters.

Brown casually walks across his paintings to reach a far corner, his clothes billowing on his coat-hanger frame and it is often an objective of the collective to simply get food into the talented artist who hungers mostly for cigarettes. A travelling man with a tendency to disappear down south into the long grass, when Brown is in town he lives in a men’s camp on the fringe of Tennant Creek in a two-roomed house with five other men, including fellow Brio artists Clifford Thompson and Lindsay Nelson.

For them, home is a tin roof, Besser brick walls and a concrete floor with no running water. Often an electrical cord threaded between the houses like a long black snake.

Marcus Camphoo, known as Double OO, is the youngest member of the Brio. Wispy and wild-eyed, the 26-year-old crouches over his paintings, thick black hair covering his face and in a way, his inner world. Solo and thickly rendered, OO’s work is geometric, grainy and strangely elusive.

Camphoo seems to live nowhere, moving between houses or sleeping out in the open, his night wanderings possibly a habit he’d picked up as a child from living in Ali Curung, south of Tennant Creek. The seventies were heady times for indigenous Australians, a time when land claims were being heard in court and the first Australians were given the right to vote and to be paid for their labor. But in towns and remote communities along this highway, liquor storeowners, grog runners and publicans were quick to exploit the times by focusing intently on the Aboriginal ‘right to drink’. By the eighties nights were often marked by wandering groups of children, looking for safe places to sleep.

Today Tennant Creek is drawing strength from its rough and ready history. Yes – it was a town built on colonization, of pastoralism and miners, missionaries and mercenaries – but there were extraordinary, lesser known fights as well – from 1860, when explorers were fought with boomerangs and bushfires to the last few decades that has seen lengthy land claims, resistance to the liquor commission and mining agreements with traditional owners all come to fruition.

Artists Jimmy Japarula Frank and Joseph Jungarayi Williams are Warrumungu men, the country on which Tennant Creek is settled. They are family men and provide a traditional element to the palpably raw, almost mongrel Brio collective. Their knowledge of wood carving and connection to culture is an anchor - and perhaps even a weave of protection for the Brio who have all, individually, lost so much. And in a town that was briefly the site of a gold rush – the cash now long gone, and built on the backbone of hard labor and droving, much of it indigenous, the Brio are a spark, a tiny piece of flint that has created a buzz – and that most fragile thing of all, hope – all around the country.

The Sydney Biennale runs from the 14th March to the 8th of June.

We have a short video which is available for licensing too. Do let Matt know if you wish to see it.

click to view the complete set of images in the archive